Old Conan fans still discuss L. Sprague de Camp (1907 – 2000) in relation to Robert E. Howard and Conan.

Mentioning his name to a gathering of fans is almost sure to drive a wedge between them; some fans believe he was single-handedly responsible for keeping Conan in the public eye long enough for the character to become a household name, and others think his involvement with the character was the worst thing that ever happened.

What did de Camp do to foster such animosity?

THE GOOD: The Rise of Conan

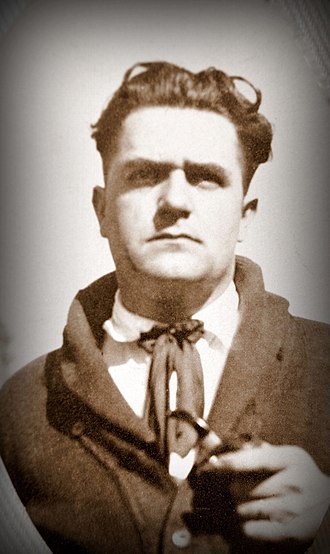

According to de Camp, he never intended to become Howard’s posthumous collaborator. “It just happened that way. I’d never even read a Howard story until 1950.” De Camp’s involvement with Conan began during the publication of the Conan hardcover books from Gnome Press. Martin Greenberg was the publisher and he brought de Camp onto the project with the third Gnome title, King Conan, in 1953. Fletcher Pratt gifted de Camp with a copy of Conan the Conqueror, Gnome’s first offering of REH material, the novel-length The Hour of the Dragon. Pratt didn’t care for Conan and passed it off to de Camp, who apparently had the same reaction as the rest of us. He wanted more.

De Camp made his way to Oscar Friend, the literary agent who was working for the Howard Literary Estate, and asked him about more Conan stories. Friend, who had acquired the literary agency from Otis Adelbert Kline, had a box of typescripts that the Kline agency had been shopping around for REH at the time of his death. Afterward, Kline continued to try and sell stories to magazines on behalf of Dr. Isaac Howard, and then when he died, the Estate Literary Rights passed on to P. M. Kuykendall, continuing the arrangement.

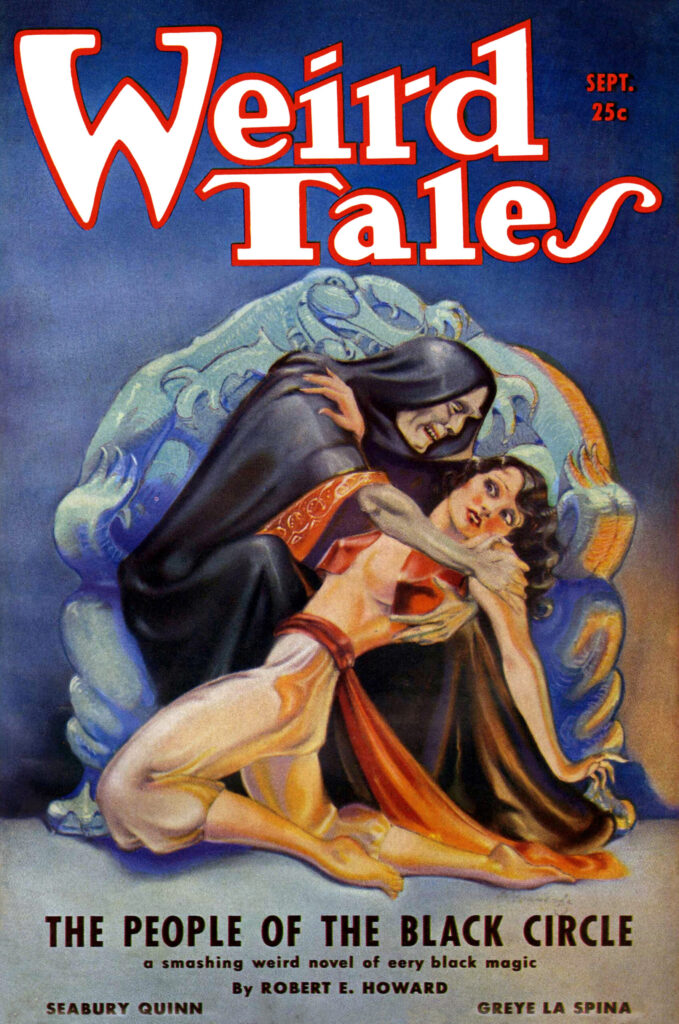

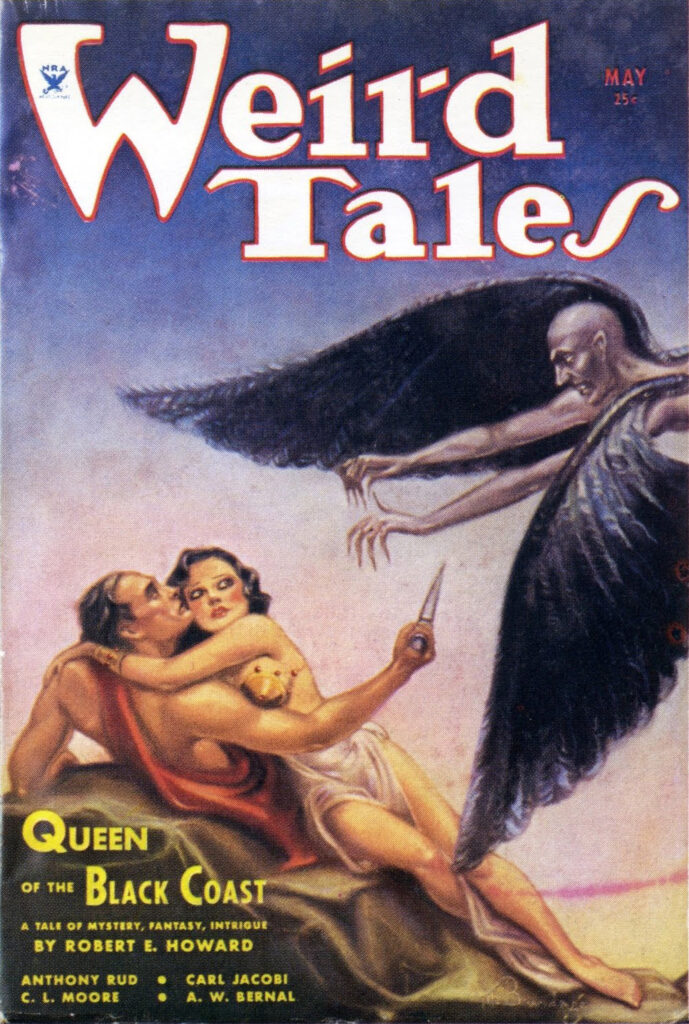

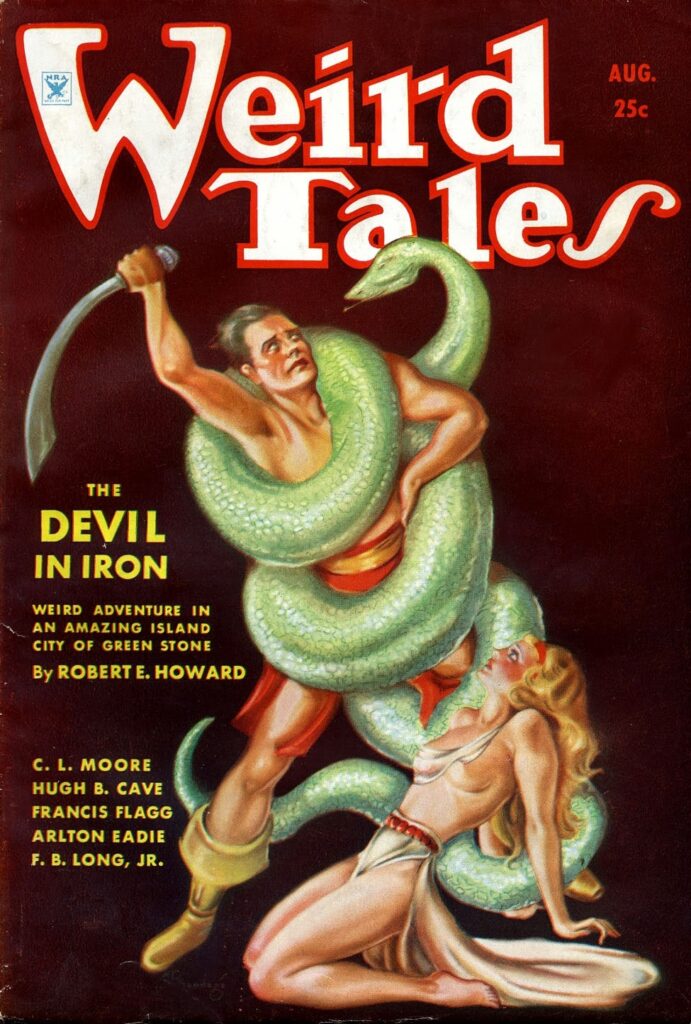

While rummaging through Friend’s box of unsold manuscripts, de Camp found and identified three Conan stories that had been rejected by Farnsworth Wright at Weird Tales: “The Frost Giant’s Daughter,” ‘The God in the Bowl,” and “The Black Stranger.” De Camp did an editorial pass on the stories, most especially “The Black Stranger”—he would revise it three times during his tenure as Conan’s editor. He significantly rewrote the story, renaming it “The Treasure of Tranicos.” Friend placed the story in Fantasy Magazine before it was included in the third Gnome Press Conan title, King Conan, along with an introduction by de Camp that explained how he came to be involved in the first place.

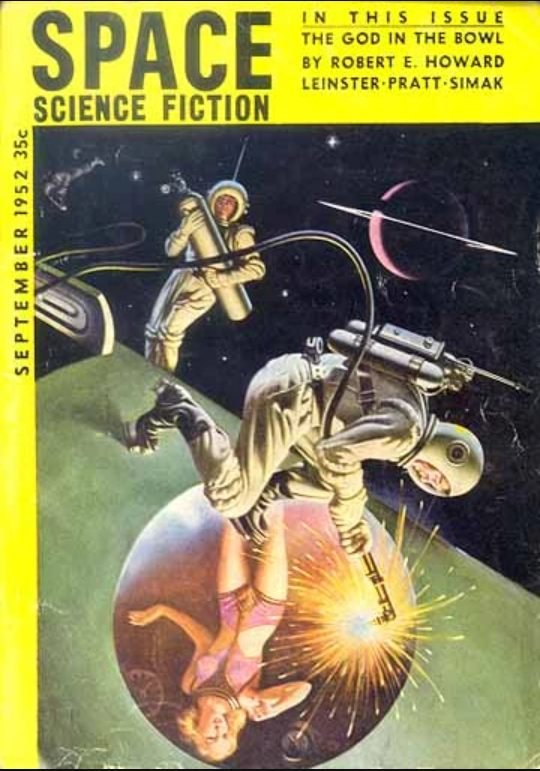

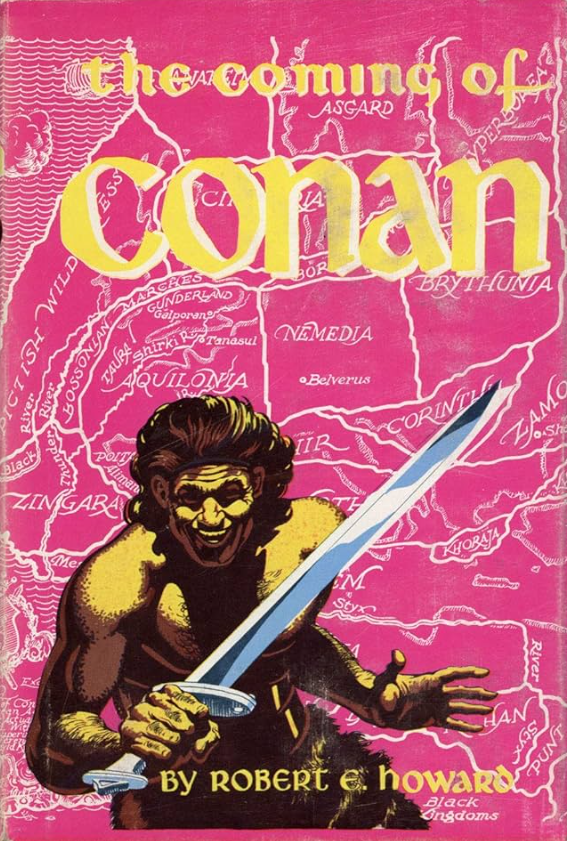

The other two stories, “The God in the Bowl” and “The Frost Giant’s Daughter,” would first be published in Space Science Fiction in 1952 and Fantasy Fiction in 1953, respectively, before finding a place in the fourth Gnome Conan title, The Coming of Conan in 1953. De Camp also provided an introduction, along with the inclusion of what would be de Camp’s longest-running commercial project: organizing the various Conan stories into a chronological saga that detailed his humble beginnings and ending with his ascent to the throne and his struggles to keep it.

Two fans of Howard’s, John D. Clark and P. Schuyler Miller, wrote an essay called “A Probable Outline of Conan’s Career” 1936 and sent it to Howard for his perusal and review. Howard replied, and this letter contains Howard’s own thoughts about where the character came from and where he potentially could have gone. This outline was first reprinted in 1938 in a small press publication by Donald Wollheim and Forrest Ackerman called The Hyborian Age and circulated among fans and admirers. Excerpts from the outline were used in prior Gnome Press volumes as an introduction to the individual stories. But now that more Conan tales had been discovered and published, de Camp, Clark, Miller, and others rewrote and expanded the timeline into “An Informal Biography of Conan the Cimmerian,” containing all of the stories in print at the time.

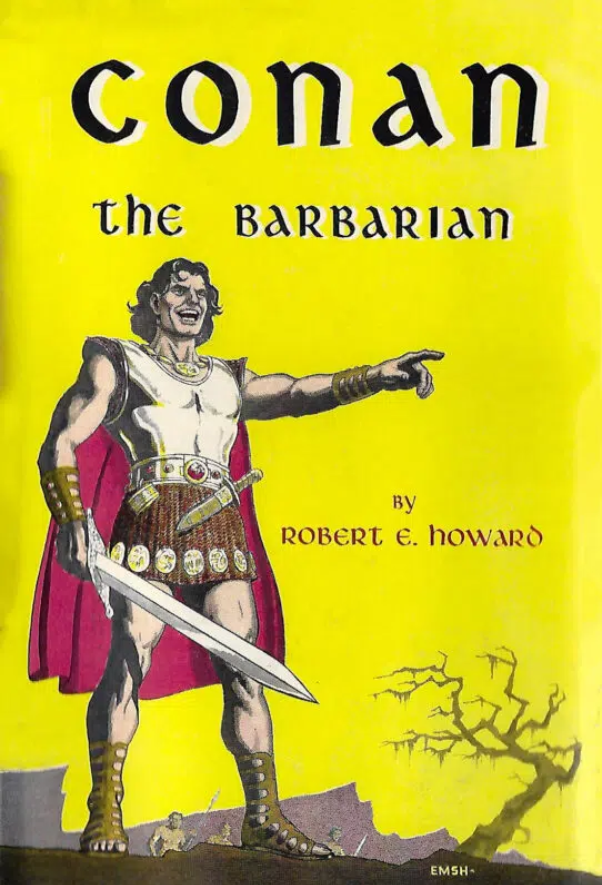

If Clark’s name sounds familiar, it’s because he was the editor for the Gnome Press line of books, and he had help in the form of de Camp and Oscar Friend, finding and revising some of Howard’s unsold works. By the fifth Gnome Press title, Conan the Barbarian, de Camp had replaced Clark as the series editor.

The sixth Conan book, Tales of Conan, was constructed out of four unsold desert adventure tales, including an El Borak and a Kirby O’Donnell story, that de Camp converted to Conan yarns, adding supernatural elements, changing all of the proper nouns, and swapping rifles and pistols for blades and swords. Three of these stories were first printed in science fiction magazines before being collected into hardcover, along with an original introduction by Clark’s friend and Howard superfan, P. Schuyler Miller.

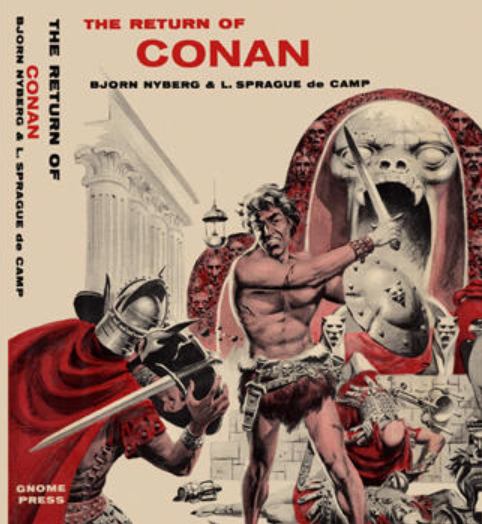

The Gnome hardcovers created enough interest in Conan that de Camp was asked about writing new stories. He told one fan “There are no more Howard tales suitable for use in the Conan series, as far as I am concerned. John Clark and I have been over all of them with a fine-tooth comb, and as you saw yourself we had gotten pretty far down in the barrel.” That soon changed when he learned about Björn Nyberg, a Swedish Air Force Lieutenant and Conan fan, so much so that he wrote a novel called The Return of Conan. Nyberg wasn’t a native English speaker, and as a result, the manuscript had, in de Camp’s words, “considerable Swedish flavor,” which he toned down with an editorial pass. The Return of Conan was Gnome’s seventh and final book.

Gnome Press had fulfilled its obligations but was always in dire financial straits, and whatever relationship de Camp had with Greenberg was damaged if not outright destroyed by late payments and non-payment of royalites owed. De Camp began searching for a home for this expanded saga of Conan he’d helped create, and it took nearly a decade before de Camp would place the series at Lancer Books—and the rest was history.

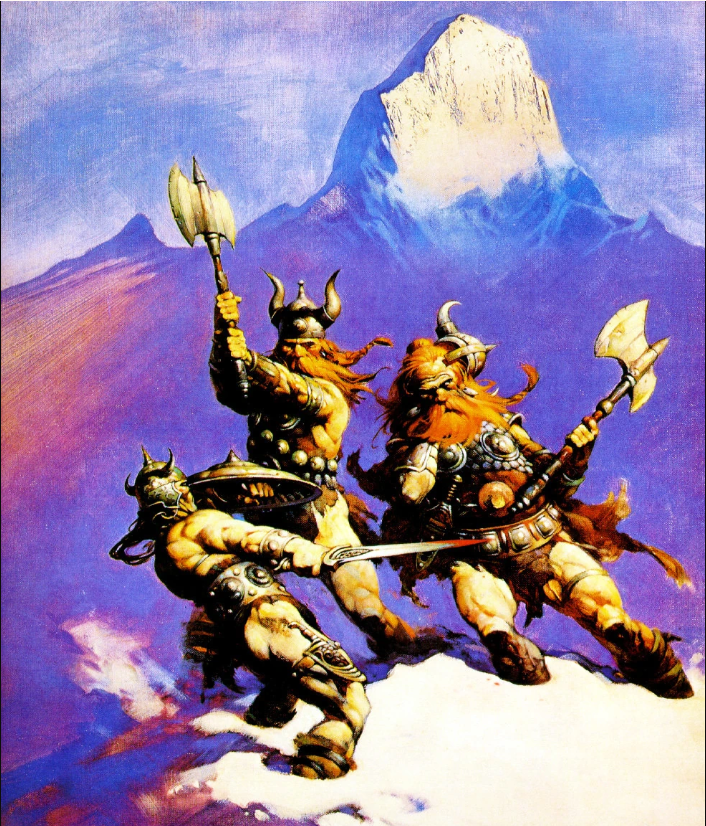

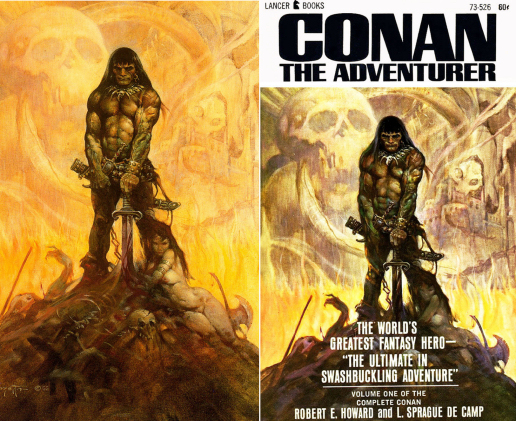

Those cheaply printed paperback books, the first of which was published in 1966, featured evocative and arresting painted covers by Frank Frazetta. The combination of Conan and Frazetta would make the Lancer Conan paperbacks a huge success. Over two million copies of the books would be sold before Lancer declared bankruptcy in the early 1970s. The series find a new home at Ace, where a total of 12 books would be reprinted and published throughout the rest of the 1970s and 1980s.

This is the beginning of “Conan the Barbarian” in the wider arena of popular culture. The widespread distribution of the Lancer paperbacks to newsstands meant that a lot of people were seeing Conan for the first time. Roy Thomas, working as an editor for Marvel Comics, brought the Conan paperbacks to the attention of editor in chief Stan Lee in 1970. The success of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian comic would lead to a second title, a black and white magazine called The Savage Sword of Conan. The character was one of the more popular Marvel heroes and was included in a number of licensing deals, right alongside Spider-Man, Captain America, and the Incredible Hulk.

Conan was on his way to becoming a pop cultural phenomenon, and the time seemed right for a Conan movie. By this time, there were two people working on Howard’s legacy: de Camp, in charge of Conan, and Glenn Lord, a literary agent who was responsible for the rest of Howard’s output.

Producer Ed Pressman was interested in acquiring the rights to make a Conan movie, but both Lord and de Camp insisted that they were the ones to deal with. Pressman threw up his hands and told them to get their story straight. The lure of Hollywood is what led to the formation of Conan Properties, Inc, with a board of directors that included de Camp and Glenn Lord. This corporation insured that all parties would be heard from and represented in negotiations. Forming CPI is what got the ball rolling on what would eventually become Conan the Barbarian (1982), starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Two movies, a Saturday morning cartoon series, a syndicated TV show, toys, video games, and so many more novels—if you bought anything with Conan’s name on it in the 1980s or 1990s, you have CPI— including de Camp—to thank for making that deal.

THE BAD: The Fall of Robert E. Howard

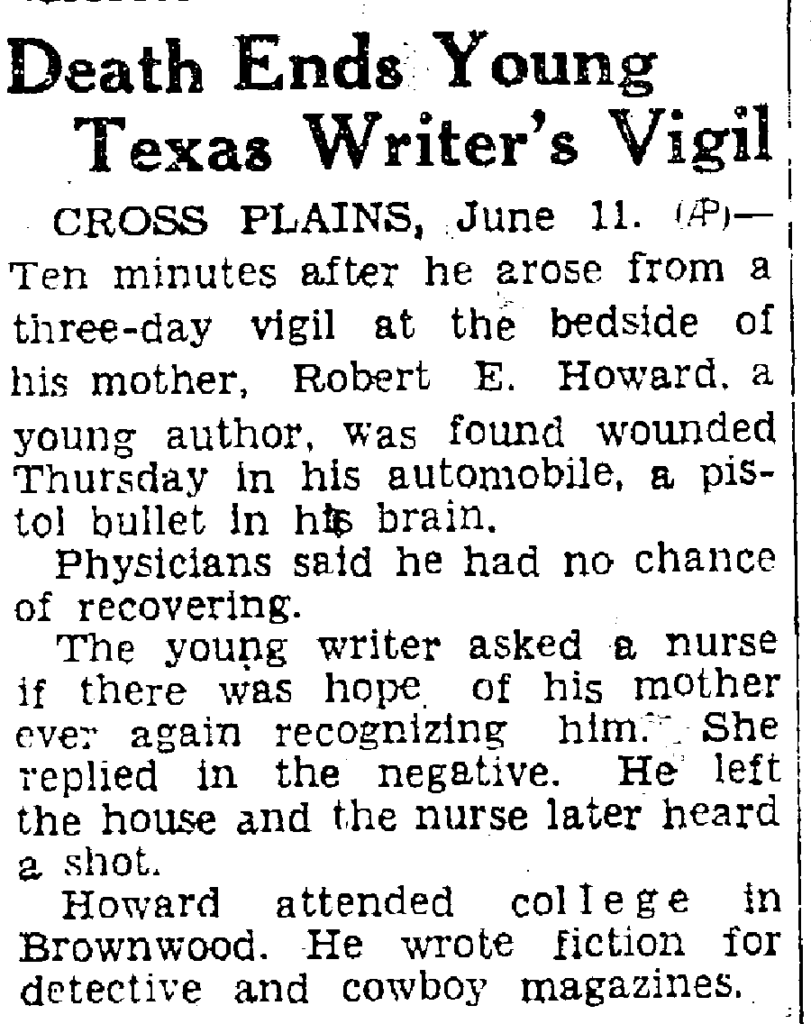

The first thing de Camp ever wrote about Robert E. Howard was a review of the Gnome Press edition of Conan the Conqueror in the April 1951 issue of the pulp magazine Astounding Science Fiction. In the second paragraph, he said:

“Howard was an almost-very-good writer who might have overcome certain limiting quirks had he not killed himself at an early age. Conan exhibits his virtues of fast and uproarious action, and of the maintenance of a high level of tension —a quality exemplified among current sf writers by Leigh Brackett. His main fault was a tendency carelessly to throw his imaginary world together anyhow, so that the poor carpentry shows.”

It’s interesting to note that even in his first review of Howard’s work, de Camp was admiring of Howard’s ability to write brisk action, but only after he offered up a critique of his writing skills and a somewhat cavalier attitude about his suicide.

De Camp repeated these sentiments and added a few more in the pages of The Science Fiction Handbook (1953), a “How to Write Science Fiction” book written by de Camp and his wife, Catherine Crook de Camp. About Howard, he added:

“Howard’s work suffered from careless haste. His barbarian heroes are overgrown juvenile delinquents; his settings are a riot of anachronisms; and his plots overwork the long arm of coincidence. Nevertheless the tales have such zest, speed, vitality, and color that the connoisseur of fantasy will find them worth reading.”

Two years later, de Camp found himself working on the third Gnome book, King Conan, and was comfortable enough to write an introduction to the book, explaining his involvement. It was the most he’d written about REH at the time, including a few insights he’d gleaned from talking to fellow writers and editors, including Harold Preece, who met and corresponded with Howard from 1928 to 1931.

“As a writer, Howard had both virtues and faults; as do the rest of us; but his were on a grand scale. Hostile critics have objected that his setting are a riot of anachronisms, his plots a tissue of coincidences, and his heroes mere overgrown juvenile delinquents. When the first collection of Howard stories appeared in book form, the reviewer for The New York Times was so alarmed by what he deemed schizophrenic tendencies of the “superman cult” that he devoted most of his review (September 29, 1946) to a warning against the perils of hero-literature and had little to say about the stories themselves.

And, without a doubt, Howard was a psychological case-study. In Conan he created a wishful idealization of himself; Conan even looked like his creator on a slightly larger scale. Howard suffered from delusions of persecution and his end constituted a classic case of Oedipus complex.”

This introduction, and many of the statements in it, are indicative of de Camp’s assessment of Robert E. Howard for roughly half a century. The mischaracterizations he’d implied as having come from other critics were things he himself had voiced in reviews. He would repeat those statements over and over, occasionally refining them, but never really changing or retracting them, in introductions, book reviews, essays and articles, interviews, and eventually, books.

De Camp was clearly interested in Robert E. Howard’s life, but he was also asking for work; he inserted himself between Oscar Friend and Martin Greenberg, acting as a subcontractor and getting paid his going author’s rate for reworking unsold Conan stories. There was a financial incentive for de Camp, and he must have liked the work because it became his professional identity for decades.

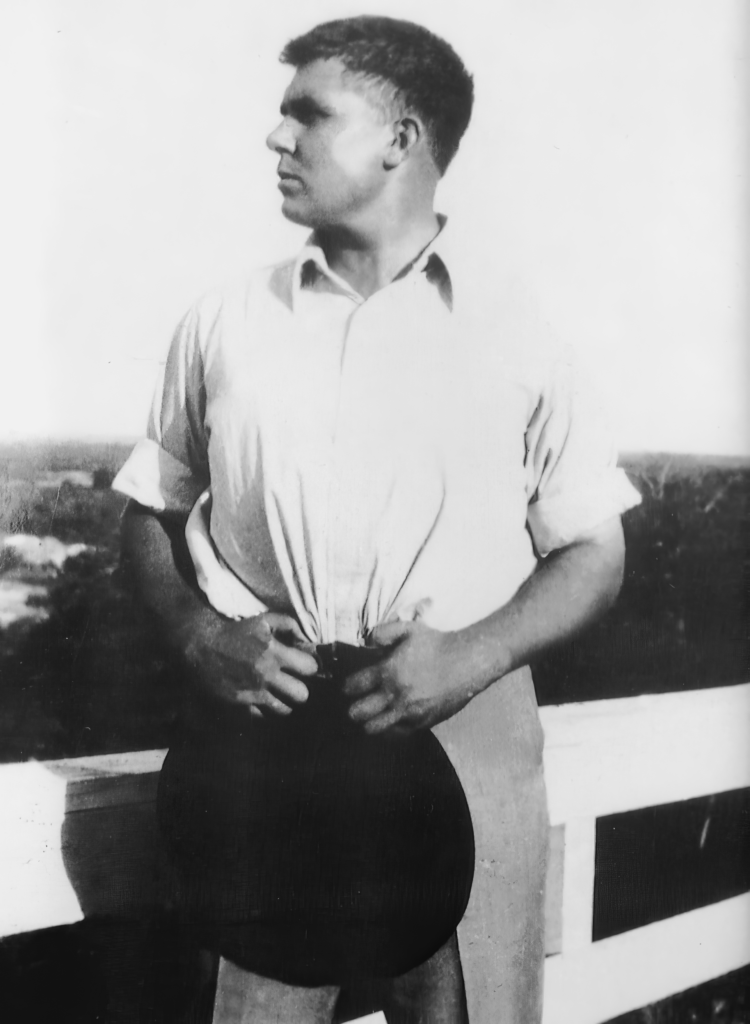

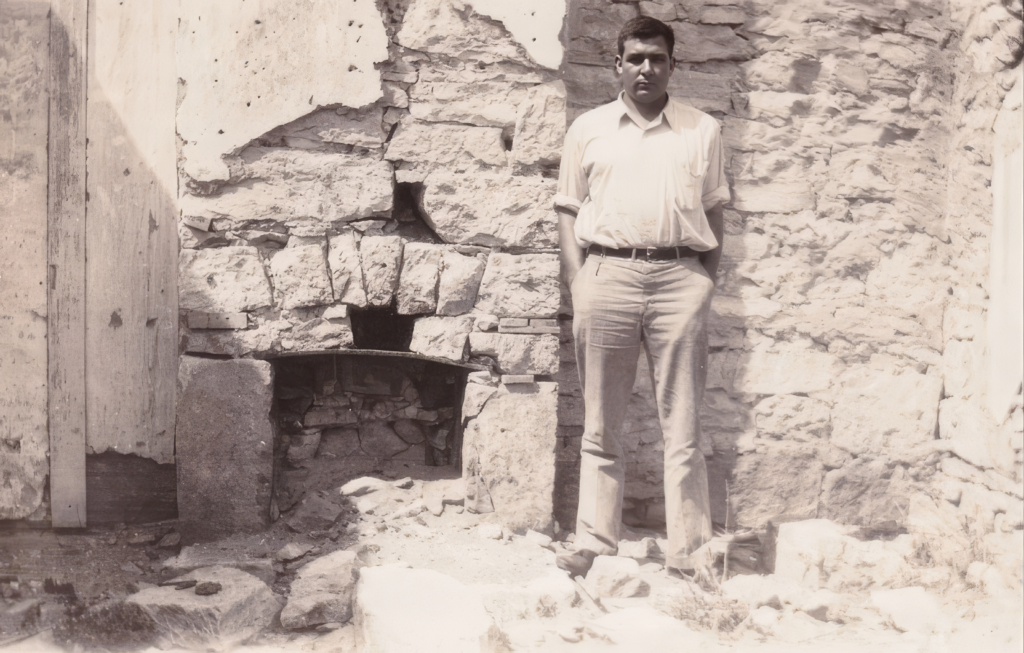

There wasn’t a lot that was known about Howard’s life at that time. Most of Howard’s correspondence was scattered across the country, as well as the contents of Howard’s literary estate, his unsold manuscripts and other papers. Howard’s friends and peers had moved on with their lives. His tragic end was fifteen years ago and they were busy with marriages, kids, and careers.

The crux of de Camp’s fascination seems to have been, “Why would someone on the verge of literary success suddenly decide to kill themselves at the age of 30?”

De Camp, then, took what few facts he had, along with the opinions of several people who knew Howard, and the psychological commentary from various detractors of Howard’s Conan—of which there were many—and formed an incomplete and skewed picture of the Texas author he’d never met. He made several assumptions about Robert E. Howard that were based more on the timeline of events rather than exigent circumstances, and presented them matter-of-factly.

As the pieces of Howard’s legacy began to coalesce; Glenn Lord was gathering Howard’s poetry for a collection of verse, and then later, his letters, and eventually, all of the unpublished material he came across. He began publishing his findings in places like Amra, the semipro zine that was one of the most successful and longest-running fanzines of all time, devoted to sword and sorcery and its practitioners and authors. This meant there was a lot of talk about Conan and his ilk, and also about Robert E. Howard.

De Camp, too, began his own investigation into Howard’s life. For the article “Memories of R.E.H.” he made a trip to Texas with science fiction writer Alan E. Nourse. While driving around Texas, trying to talk to Howard’s friends, Nourse, who was not a psychologist, and also not a fan of Robert E. Howard or Conan or sword and sorcery, was quick to share his opinions with de Camp as to Howard’s mental state.

Upon learning from Tevis Clyde Smith that Howard used to sleepwalk at night, de Camp wrote that Nourse, “… as a physician, pointed out that Howard’s history provided a classic case of sexual maladjustment, such as is often initiated by the combination of a domineering, coldly hostile father and an overprotective mother. ‘That sleepwalking alone,’ he said, ‘indicates a profoundly neurotic personality—probably hysteric and hypersuggestible. You add to these other factors the fact that he was only starting to take an interest in women when he was nearly thirty, and that exaggerated interest in manly sports—well, it’s obvious that here was a fellow who wasn’t wired up just right in the matter of sex.’”

By the time the Lancer paperbacks were published, starting in 1966, de Camp had written dozens of articles about Howard and Conan, and he had assembled a biography of REH based on his musings, assembled using lines from all of his own previous writings. The longer de Camp worked with Conan and edited, rewrote, co-wrote, and spoke about Conan and Robert E. Howard, the more he dug in on his own personal opinions about Howard.

Eventually, de Camp’s thoughts and theories, his misconceptions and intentionally worded statements, were published in the millions, first in the Lancer paperback series from 1966 to 1974, and then later in the Ace paperback series from the mid-1970s into the late 1980s. There wasn’t a Conan fan who discovered REH from the 1950s to the 1990s that didn’t have to read and re-read de Camp’s inaccurate and distorted portrait of Robert E. Howard: weak, puny, bullied as a child, grew up with feelings of persecution, and paranoid about imaginary enemies, maladjusted to the point of psychosis, and who, had he not killed himself in a fit of despair over the death of his aged mother, to whom he was unnaturally devoted, he might have made the transition to “full dress” professional writer, if only he had shed some of those amateur bad habits.

That’s not to say that these slings and arrows went unchallenged. Starting in 1975, fans and professionals alike were pushing back on de Camp’s narrative of Howard’s life in various REH-related fanzines. One of Howard’s old friends, Harold Preece, whom de Camp met decades ago and first developed his theory about Howard’s so-called Oedipus Complex, would start his scathing review of de Camp’s biographical sketch, The Miscast Barbarian, with this opening salvo: “Currently a prominent author with a marked streak of Texaphobia, L. Sprague de Camp, has attempted what amounts to a once-over lightly interpretation of a writer whose complexities he often treats with lordly condescension and rather facile psychological jargon.”

De Camp was a practiced hand at dealing with irate fans and thorny personalities, and he gave as good as he got; he spent the remaining 25 years of his life defending the things he’d said about Robert E. Howard. This culminated in the publication of Dark Valley Destiny in 1983, the first book-length biography of Robert E. Howard, written by de Camp, his wife, Catherine, and a Texas-born child psychologist named Jane Whittington Griffin. In it, de Camp repeated all of the previous erroneous statements he’d made over the years. To compound his error, he made all new ones, as well.

The de Camps used Griffin and her thick Texas drawl to open doors that they themselves would have found closed in their faces. They managed to interview some of the last people to know the Howards as a family, including one of Mrs. Howard’s nurses at the end of her life. They asked a lot of questions of these people, and in particular, they repeated the same questions to everyone, over and over, looking for a different answer than the one they were initially given.

The best example of this is the number of times they asked their interview subjects if they remembered Howard ever being sick as a child; puny, in ill health. They stated it many times in different ways. De Camp’s wife Catherine kept returning to it, over and over, so much so that de Camp finally admonished her to “let the woman speak.” They found no instances, from any of the interviewees, that Howard had a lingering illness of any kind. De Camp even supposed that it kept Howard out of elementary school—another wrong conclusion.

Nevertheless, despite asking everyone they interviewed, many times, with no evidence to the contrary, this can be found in Dark Valley Destiny: “Frail, introverted, and looking to his mother for protection, Robert was a natural butt for bullies. Even before the opening of school, every day saw a series of terrifying encounters, which varied from the merely mean to the inquisitorial. He could not leave his yard for fear of being set upon. The fact that his mother read extensively to him, and in so doing enhanced the closeness already established, only made matters worse.”

There are a lot of other things de Camp said, and whether we’re talking about the biography or any of his introductions or articles, he was always sure to include a paragraph that said something along the lines of: “Despite certain literary faults, Howard was one of the greatest natural story-tellers the genre has produced. Nobody has excelled him in constructing a fast-moving, smoothly-flowing tale of headlong, violent, gripping action. His stories are not only readable but also endlessly rereadable.” Sometimes this backhanded compliment came before the line “maladjusted to the point of psychosis” and sometimes after, but they were never far apart.

THE UGLY: Behind-the-Scenes Skullduggery

Oscar Friend wrote to P. M. Kuykendall in March of 1954, around the time that de Camp took over as the editor for the Gnome Press book, Conan the Barbarian that included the following warning:

“There is one smart writer now who has been doing some work for us in rewriting several Howard stories, and he keeps pressing for a larger cut and keeps slipping in side remarks to the effect that if he wants to he can and will go ahead on his own and write about Conan as the author is dead, etc., etc. And I’ve warned him that I’ll sue the pants off him if he makes one silly move of this nature before the CONAN material runs out of copyright…”

Of course, he was talking about de Camp, who had been paid for his editing duties on the unsold Conan stories (we don’t know how much, but it seems from the various letters and interviews that de Camp was paid his “going rate” for writing), paid for his converting of unsold desert adventure stories into Conan tales, and possibly for penning an introduction or two. Not bad for a character and some stories he had nothing whatsoever to do with initially.

De Camp filed the copyrights on the rewritten Howard stories he’d worked on, as a co-author, no less. He could do this because in the “editing for publication” of the unsold Conan stories, de Camp only had to alter 10% of the story to qualify it as a new version. Some of de Camp’s edits were nothing more than rearranging sentence subjects and objects and other grammatical assists, but ten percent is ten percent. Some stories, like “The Black Stranger,” got more edits, and considering how many times he reworked his “The Treasure of Tranicos,” approximately 40-50% of the story was rewritten by de Camp.

After Gnome Press published The Return of Conan in 1957, there was a discussion about whether to continue writing Conan stories. Greenberg wanted to approach Leigh Brackett, who was busy in Hollywood writing screenplays for Howard Hawkes, but by this time, Gnome (Greenberg) had developed a reputation for paying late, or not at all, his writers and artists, de Camp included, and she declined the offer. De Camp and Greenberg were on the outs, as well, and it was pretty public, creeping into de Camp’s book reviews in other magazines as a snarky aside or two.

Despite middling to weak sales of the books, the idea of reprinting the Conan books in paperback came up. Greenberg maintained that he controlled the copyrights, despite alleged non-payment of royalties on the books. Eventually, de Camp took Greenberg to court to wrest all of the publishing rights away from Gnome, and the lawsuit dragged out for several years.

From 1959 to 1963, the copyrights on the original seventeen Conan stories printed in Weird Tales expired. De Camp quietly filed copyrights on the stories he had edited. He also managed to get his hands on several incomplete fragments and outlines for unwritten Conan stories. On the advice of his lawyer, and to strengthen his position in the ongoing litigation, de Camp completed these bits and pieces from the unsold Howard manuscript cache, roping in a co-writer, notably, Lin Carter. These “posthumous collaborations” were sold to magazines who were happy to include Robert E. Howard’s name on their cover, even if it was part of a list of co-authors.

On his own initiative, de Camp began shopping the Conan Saga to other paperback publishers. Accounts vary on who passed and why, but the lawsuit with Greenberg surely played a part in several larger publishers saying no thanks. That’s likely how the Conan books ended up at Lancer and not someplace like Ace. In fact, de Camp told Oscar Friend’s daughter, Kittie West, after he’d already made the deal. West commented, in a letter to Glenn Lord about the situation, “Sprague getting greedy?” As the lawsuit was coming to a close (de Camp won a summary judgement), Oscar Friend’s literary agency that had represented the Howard literary estate was closing up shop. Kittie West offered de Camp the job of literary agent for Kuykendall’s wife, Alla Ray Kuykendall, and daughter, Alla Ray Morris.

By de Camp’s own estimation, the amount of material he’d helped create in the Conan books was approximately 50% of the contents, including several novels that had nothing to do with Robert E. Howard.

Since de Camp had been getting paid for his writing and editing, he refused, stating that he didn’t want the appearance of impropriety—such as double dipping, by taking an agent’s commission and also getting paid for writing new material. He agreed to represent Conan, however, as he had already done so much in this respect. For everything else he recommended Glenn Lord as an agent, as their paths had crossed several times, cordially and convivially in the pursuit and collecting of the various pieces of Howard’s literary estate. De Camp was now free to make the best deals he could for himself, for Conan, for the heirs, and for Robert E. Howard. In that order.

By the mid-1970s, Lancer was in financial trouble, as well, and de Camp sued them for unpaid royalties. De Camp himself was also taken to court by Glenn Lord, seeking unpaid royalties on behalf of the literary estate for foreign language editions of the Conan books, another deal de Camp brokered. They settled out of court, but whatever relationship they had was now contentious, which was the reason for both Lord and de Camp trying to make a movie deal without the other one involved.

Once Lancer was out of the picture, Glenn Lord tried to publish the unaltered Conan stories as they first appeared in Weird Tales, with introductions by noted sword and sorcery author (and REH fan) Karl Edward Wagner. This was part of a larger deal that Lord made to include Howard stories that had been published during the “Howard Boom” of the 1970s. De Camp, through CPI, scuttled the deal after the first three volumes appeared.

The Ace paperback series picked up where Lancer left off, adding a twelfth non-Howard Conan title to the Official Conan Saga. The series was expanded to include new novels by various hands. Of course, de Camp and Carter were writing some of the books, but other authors, like Poul Anderson, Andrew Offutt, and Karl Edward Wagner. In the 1980s, Robert Jordan, Leonard Carpenter, John Maddox Roberts, Roland Green, Steve Perry, and others. Tor alone published over 20 pastiche novels featuring Our Favorite Barbarian between 1980 and 1990.

Conan had become a cottage industry under de Camp’s stewardship. De Camp would allow just about anyone to have a chance at writing their own Conan novel, except, maybe, for Robert E. Howard. Several attempts were made to get Robert E. Howard’s Conan back in print, but the de Camps and the lawyer who sat on the board at CPI regularly formed a two-thirds majority against anything that didn’t include all of de Camp’s previous additions to the intellectual property. Glenn Lord was able to place a line of paperbacks at Baen that including many of Howard’s other series characters, such as Solomon Kane and Bran Mak Morn, but this only raised more questions: where was REH’s Conan? The de Camps played hardball in this fashion until their passing in 2000.

Final Thoughts

It’s tempting to liken de Camp as being Rufus Griswold to Robert E. Howard’s Poe, or more accurately, the August Derleth to Howard’s H.P. Lovecraft. While the Griswold analogy is apt with regard to de Camp’s handling of Robert E. Howard and his personal life, I don’t think it was done with malice aforethought. What is certain is that Howard’s biography would have been presented very differently, and this is the real heart of the matter. De Camp himself admitted he exhibited a certain “intellectual arrogance,” borne out by a cursory examination of most of his professional writing.

Insofar as Derleth founded Arkham House and physically kept Lovecraft’s work in print for years, there’s a kind of parallel to that analogy, but it’s worth noting that had de Camp not become enamored with Conan after the first Gnome book was published, the rest of the books would have been published anyway, as the deal was done before de Camp happened along.

It’s been argued that de Camp rescued Robert E. Howard from obscurity, but this presupposes that there were no other Conan fans in the publishing community. Would Conan’s revival have happened the same exact way?

Well, no, of course not, but it’s not impossible to guess how the series would have developed. Donald Wollheim was a fan of Howard’s, and not just his Conan stories. Ace would have been a fitting home for any and all REH paperbacks. It was a happy accident that de Camp took the series to Lancer and they offered Frazetta a better deal than Ace—he got to keep his original paintings. De Camp didn’t like Frazetta’s “long-haired Hippie” depiction, but he was thankfully overruled.

Regardless, this issue is ancient history. In the last 25 years, we’ve seen a number of positive changes regarding Howard’s stories and poems and how the facts of his short life have been handled. Four biographies have been published since 2006. The first of three volumes of Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories saw print starting in 2003 from Wandering Star. All of Howard’s writing—not just Conan—is available in print in some form. And Conan has been correctly associated with Robert E. Howard, while other authors’ works set in the Hyborian Age are now considered separate from the canon.

L. Sprague de Camp will continue to come up in conversations, but his role can’t really be debated. He said what he said, and he did what he did. And we got what we got. It’s in the past. The only real question you have to ask yourself is how you feel about de Camp’s actions. I would suggest that it matters less and less, considering we are so far down the road and there more positive things to focus on right now.

Conan has survived all of that and more, and we’re still reading and enjoying his exploits. New readers are discovering Conan in a variety of ways, including books, comics, games, toys, artwork, and more, and it all points back to Robert E. Howard. I think both he and Conan would be pleased to see that.

Mark Finn

Mark Finn is the author of Blood and Thunder: The Life and Art of Robert E. Howard, and a great many other books, essays, comics, short stories, and tabletop rpgs, as well. He lives in North Texas over an historic old movie theater with his wife and a ridiculous amount of books.