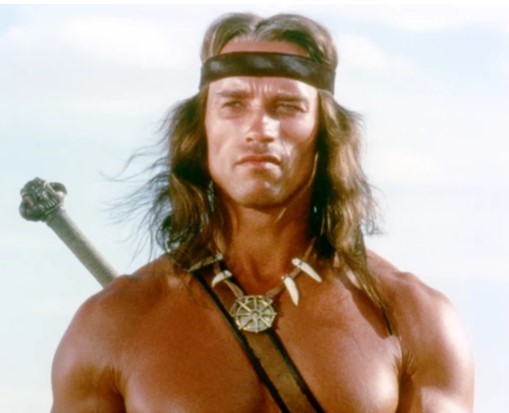

You know the scene. A boy becomes a machine becomes a man, and somewhere in that grinding transformation lies one of sword and sorcery cinema’s most haunting images.

John Milius’s Wheel of Pain from Conan the Barbarian (1982) has spawned decades of analysis, interpretation, and debate among scholars, critics, and fans who recognize the wheel as a masterclass in visual storytelling.

To engage more with the question of “What is the symbolism of the Wheel of Pain?” we’ve borrowed and aggregated analyses from a deep well of sources including Deep Focus Review, Reflections on Film, The Philosophy of Arnold blog, The Symbolic World, the Film School Rejects, The Rumpus, and even merchandising perspectives from Comic Book Shop. These sources all circle back to the same conclusion: there’s far more happening in those few minutes of screen time than just “Conan gets strong.”

Let’s unpack.

Symbolic and Allegorical Interpretations of the Wheel of Pain

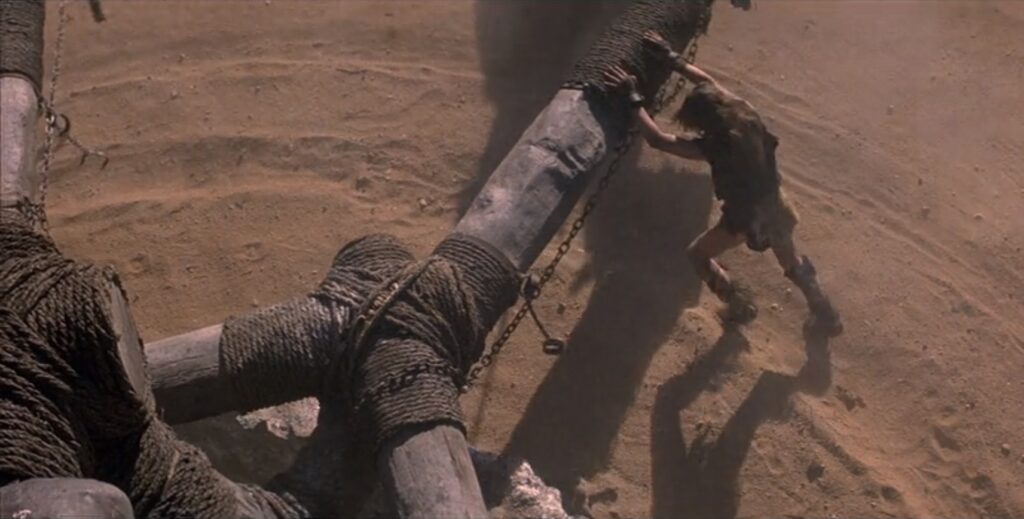

The Wheel of Pain is laden with symbolic meaning. On a surface level, it serves to plausibly explain how Conan became so formidably strong – he has literally been engineered by unceasing labor.

However, John Milius intended the Wheel chiefly as allegory, representing universal human struggle. He likened it to the “fruitless toil of life” itself. Indeed, the image of innocent youths condemned to push a mill in endless circles evokes mythic and literary parallels, such as the Greek myth of Sisyphus eternally rolling his boulder. Like Sisyphus’s task, Conan’s grinding labor at the Wheel appears absurdly cyclical and unending.

Critic John Kenneth Muir observes that the Wheel of Pain sequence functions as “a perfect metaphor for the human existence,” translating Conan’s specific suffering into a broadly relatable image of repetition and hardship that many can recognize in aspects of their own lives. In this way, the Wheel transcends its fantasy setting to comment on the human condition in any era.

Significantly, the film is prefaced by a famous aphorism from Friedrich Nietzsche: “That which does not kill us makes us stronger.” This epigraph announces a core theme of strength through suffering, which the Wheel of Pain dramatizes. Under a Nietzschean reading, Conan’s ordeal is a brutal apprenticeship that ultimately toughens and “re-creates” him. The Wheel can be seen as turning Conan into a kind of Übermensch figure – a self-made man of supreme physical and mental resilience. His identity is forged on this wheel just as surely as the steel of his father’s sword was forged in fire at the film’s opening.

It is no coincidence that young Conan wears a circular emblem – the Wheel’s sigil – as a pendant around his neck during his enslavement. That emblem literally marks the wheel’s imprint on his identity. He is a child of the Wheel, effectively constructed by this experience. In symbolic terms, the Wheel of Pain “creates one [man]” even as it destroys many. Most who are chained to it perish in vain, but the rare survivor emerges “harder and stronger than any weapon of steel”.

The circular form of the Wheel invites further allegorical interpretation. Circles and wheels traditionally symbolize cycles of time, fate, or fortune. In medieval allegory, the Wheel of Fortune turned to raise some people up and cast others down. Conan’s Wheel of Pain could be seen as a grim parody of that concept: it is an inverted Wheel of Fortune that keeps the lowly low, grinding its victims into the dust. Yet in Conan’s case the wheel does elevate him, turning a bereaved, powerless child into a formidable adult who will eventually overturn the social order that enslaved him.

The film pointedly shows Conan literally pushing the wheel “through sunlight and darkness, through winter and spring”, underscoring that years of time and seasonal cycles are encapsulated in this turning wheel. By enduring this long cycle of pain, Conan essentially outlasts fate; the wheel that initially symbolizes oppressive stasis becomes the very engine of his liberation. When Conan is finally unchained, he steps away as a self-made warrior, having taken what was “supposed to be an allegory” of endless servitude and, through his survival, subverted it into a story of empowerment.

Class, Labor and Self-Making through the Wheel of Pain

Beyond its mythic dimensions, the Wheel of Pain can be read in socio-political terms as a representation of class oppression and the forging of identity through labor. Conan begins life as a freeborn youth in a small Cimmerian village, effectively a member of the rural peasantry in this fictional world. When Thulsa Doom’s warlord cult slaughters the village and enslaves its children, Conan and his peers are plunged to the lowest rung of the social hierarchy: they become enslaved laborers, treated as expendable human fuel for a war machine.

The Wheel of Pain itself is emblematic of a slave economy. It is a labor device powered by human bodies, extracting value (in the form of milled grain, or simply “productive” motion) at the cost of those bodies’ lives. The film makes clear that those chained to the wheel are “only freed from the wheel once they [are] bought, or once they gave up and died from the physical demand of the mill”. In short, the wheel will literally consume a slave’s life until there is nothing left.

Within this interpretive frame, Conan’s decades on the wheel mirror the experience of an oppressed underclass subjected to ceaseless menial toil. The grinding circular motion signifies not only futility but the entrapment of the laboring class in a cycle of exploitation. There is no upward mobility on the Wheel of Pain, only the grind. We can discern a critique of class here: Conan’s youthful world (the simple freedom of village life) is destroyed by a predatory elite (Doom’s raiders), and he is literally chained to their engine of production. The food he grinds (if indeed the mill produces flour) would feed the forces of his oppressors – a stark metaphor for how slaves and the lower classes sustain the very powers that subjugate them.

Crucially, Conan’s emergence from the wheel as a singularly strong survivor can be seen as a commentary on individualism and the power of ego. In the film’s quasi-Nietzschean, libertarian ethos, Conan does not become powerful due to noble birth or divine favor, as he is literally a self-made man. The wheel is the brutal teacher that gives him that opportunity. The sociopolitical implication is that true strength and leadership are forged in the crucible of struggle, not inherited by privilege. Conan’s journey thus refutes any notion of a “natural” ruling class, and instead posits instead that greatness can come from the lowest class, through the harsh egalitarian trial of pain which either breaks a person or makes them unbreakable. In this light, the Wheel of Pain functions as a dark parody of a school or training ground for the underclass – one not designed for their uplift, but inadvertently producing a champion of the oppressed.

What is clear in the Wheel of Pain sequence is an implicit valorization of endurance and willpower. The film’s stance is not overtly political in a contemporary sense – it does not, for example, lecture about slave rights or lead Conan to incite a slave rebellion (his revenge is personal, not some kind of proletarian revolution). However, the imagery speaks volumes: the audience’s sympathy is firmly with the enslaved youth and against the cruelty of the system that exploits children in this way. In a subtle sense, this positions Conan as an avatar of the downtrodden everyman who rises up because of a great wrong done to them, not necessarily to everyone. His subsequent adventures can be seen as extensions of that initial scenario of class injustice set up by the Wheel.

Later Adaptations and Legacy of the Wheel

It is telling that the 1982 film’s invention of the Wheel of Pain has no direct precedent in Robert E. Howard’s original Conan stories. In Howard’s lore, Conan was never enslaved as a child; he grew up free among the Cimmerians and faced hardships of a different nature. The Wheel of Pain, along with the “Riddle of Steel,” was introduced in the film’s screenplay by John Milius (building on elements from Oliver Stone’s earlier draft). This creative addition proved so iconic that it has influenced later adaptations and Conan-related media, even when those adaptations diverge from the film’s plot.

For example, the survival video game Conan Exiles (2018) incorporates the Wheel of Pain as a gameplay mechanic for “breaking” captured thralls into servitude. The official game lore describes the wheel as “a wheel that strengthens the body as it breaks the mind” – a direct reflection of the dual physical/psychological effect seen in the film. Players in that game must feed their slaves gruel and have them push the Wheel until their will is subjugated, a dark tribute to the concept introduced in 1982. The very phrase “Wheel of Pain” has thus entered the broader Conan lexicon, instantly evocative of the notion of brutal training through suffering. Merchandise and pop culture references likewise acknowledge it as “a symbol of Conan’s resilience… a reminder of the trials faced and conquered”.

Interestingly, when a new Conan the Barbarian film was made in 2011 (starring Jason Momoa), the writers pointedly did not include the Wheel of Pain sequence. In that reboot, Conan’s youth involves different trials (he is raised by his father, then embarks on vengeance after his father’s death, with no intermediate slavery segment). This choice highlights a shift in storytelling priorities. The 2011 film, by omitting the Wheel, forgoes the allegorical element that the 1982 film so powerfully delivered. The result is a more conventional hero who gains his skills adventuring, as opposed to earning them through long oppression..

Even within the 1982 film’s own narrative, the legacy of the Wheel is felt long after Conan leaves it. A particularly insightful fan analysis (drawing on Milius’s commentary) suggests that Conan’s years of discipline at the Wheel granted him a kind of inner control – mastery over fear and pain – that later starts to erode when he abandons that austere mindset. After Conan obtains wealth (stealing the Eye of the Serpent gem) and replaces his wheel-forged slave pendant with a flashy token of success, he becomes more emotional and arguably loses some of the stoic focus the Wheel had given him.

This reading implies that the lessons of the Wheel were the very qualities that elevated Conan, and when he drifts from them he is spiritually diminished. It is a nuanced point: the Wheel’s value was not only in building Conan’s strength, but in imparting a philosophy of perseverance that is easy to forget once luxury or vengeance distracts him. In this sense, the Wheel of Pain stands as a permanent psychological fixture in Conan’s life. He carries the imprint of that suffering even into kingship (the film’s epilogue famously shows King Conan “upon a troubled brow” – hinting that the restlessness instilled by the wheel never entirely leaves him).

The Wheel Keeps Turning

Forty-plus years later, the Wheel of Pain remains cinema’s most potent metaphor for the paradox of suffering as creation. It’s a sequence that rewards rewatching, especially once you understand the layers Milius embedded in those few minutes of screen time.

Every element works in service of meaning: Poledouris’s mournful score, the seasonal montage showing time’s passage, the gradual disappearance of the other children, even Conan’s circular pendant marking him as property of the wheel. It’s filmmaking as philosophy, genre cinema operating at the highest level.

So here’s your assignment: Go back and watch Conan the Barbarian (1982) again. Skip the nostalgia and the camp factor for a moment. Watch it as the meditation on human will and systemic oppression that it actually is. Notice how that wheel keeps spinning long after Conan walks away from it, in his psyche, in the film’s structure, in the very rhythm of his revenge.

Because once you see it, you can’t unsee it. The wheel is everywhere, and we’re all pushing something.

Lo Terry

In his effort to help Heroic Signatures tell legendary stories, Lo Terry does a lot. Sometimes, that means spearheading an innovative, AI-driven tavern adventure. In others it means writing words in the voice of a mischievous merchant for people to chuckle at. It's a fun time.