“Now they will know why they are afraid of the dark.”

With these words, delivered in that unforgettable bass voice, James Earl Jones cemented Thulsa Doom as one of fantasy cinema’s most compelling villains.

As Shawn Curley explores in his insightful video deep-dive into the character, this shape-shifting sorcerer from 1982’s “Conan the Barbarian” has become so ingrained in popular culture that many fans assume he was always Conan’s arch-nemesis in Robert E. Howard’s original tales.

But time tells another tale.

Building on Shawn’s excellent breakdown, we’ll further explore the fascinating duality of Thulsa Doom – from Howard’s brief but influential creation to Jones’s mesmerizing screen presence – and examine how both versions have shaped fantasy villainy for decades.

Howard’s Original Conceptions of Thulsa Doom

Thulsa Doom was never intended to be Conan’s nemesis. In fact, he never even existed in the same era!

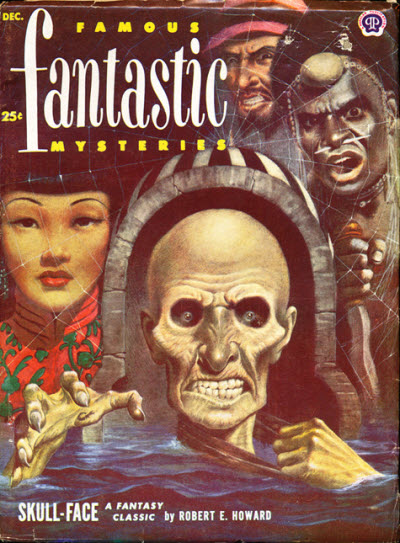

Robert E. Howard first introduced this sinister character in “Delcardes’ Cat,” a story featuring King Kull of Atlantis, who predated Conan by thousands of years in Howard’s chronology. Even more surprisingly, Thulsa Doom’s creation seems almost like an afterthought.

Howard scholar Patrice Louinet reveals that “when Howard was writing it at some point, he wanted the bad guy to be a slave named Kathulos, and at page 22 he decided no, and there’s going to be this skull-faced character. So what he did, he simply went back and he added a few references to Thulsa Doom and that’s it. That’s how the character was born.”

Despite this seemingly casual introduction, Howard created something enduring: an ancient skull-faced sorcerer with fiery eyes who appeared truly immortal. “Doom appears to be impervious to harm,” notes Howard scholar Jeffrey Shanks, “boasting that he only feels a slight coldness upon injury and that when his time does come, he’ll simply pass on to some other sphere.”

This is particularly fascinating because while Howard purists often downplay Thulsa Doom’s significance due to his brief appearances, his impact on fantasy literature has been notable. His powers were described more than shown – “we don’t really get to see a whole lot of his powers, he’s mostly doing ventriloquism” – yet Howard established him as “one of the most powerful sorcerers of the Thurian Age.”

Some Howard scholars have even speculated that another character, Kathulos of Atlantis from the 1929 novella “Skull-face,” might be Howard recycling the Thulsa Doom concept.

As Curley notes, “In 1929, ‘Skull-face’ introduces us to an ancient skull-faced sorcerer named Kathulos of Atlantis who appears in the 1920s after a very, very long nap with a thirst for world domination. Sound familiar?”

While we can’t confirm Howard’s intentions, the parallel is striking.

Thulsa Doom in Conan the Barbarian 1982

When John Milius began developing “Conan the Barbarian,” his approach to Thulsa Doom underwent radical transformation. Initial pre-production sketches depicted the villain with his classic skull face from the comics, but this idea was quickly abandoned. Instead, the film presents a Thulsa Doom more inspired by Thoth-Amon, a classic Conan adversary devoted to the serpent god Set.

“The movie’s portrayal of Thulsa Doom underwent significant evolution throughout Milius’s script revisions,” explains Curley. “He transitioned from a demonic entity in Oliver Stone’s initial drafts to a charismatic cult leader.” This transformation was heavily influenced by the late-1970s cultural context, with Milius drawing inspiration from real-life cult leaders like Jim Jones and Charles Manson just over a decade after the cult panic that shocked America.

Enter James Earl Jones, whose classical theater training would elevate this reimagined villain to legendary status. Jones himself cited Shakespearean epics as a major influence on his performance, bringing a gravitas to Thulsa Doom that transcended typical sword-and-sorcery fare.

This theatrical power is evident in Doom’s philosophical monologues, particularly the famous “Riddle of Steel” speech that forms the ideological core of the film. When Jones intones, “Steel isn’t strong, boy. Flesh is stronger,” he’s doing more than delivering lines: he’s sermonizing, drawing viewers into Doom’s twisted worldview just as his character seduces followers within the film. As Gerry Lopez recalled, “He didn’t have any kind of microphone or anything. Everybody in that crowd could hear him speak.”

In the video, Curley observes that Jones’s “voice is so intense and charismatic and you believe that the cult of set is as powerful as it is because of his presence.” This charisma is what separates Jones’s Doom from Howard’s original creation. Where the literary Doom relies on supernatural powers and immortality, the cinematic version wields something potentially more dangerous: the power to inspire devotion.

Comparing Howard’s and James Earl Jones’s Portrayals of Thulsa Doom

The contrast between these two versions of Thulsa Doom offers fascinating insight into different approaches to creating memorable antagonists.

Howard’s original Doom represents cosmic horror – an implacable, inhuman force that cannot be reasoned with or truly defeated. He exists beyond his physical form, possessing “some existence beyond his physical existence, almost like an astral form that can move on to other dimensions or can transcend his physical body.”

Jones’s portrayal, however, taps into a more insidious fear: the charismatic leader who can bend others to his will through persuasion rather than force. “What would your world be without me?” Jones asks in one chilling scene. His Doom doesn’t need to be immortal because he lives through his followers, making him potentially more dangerous than his literary counterpart.

This distinction is reflected in their methods as well. Howard’s Doom relies on sorcery and manipulation from the shadows, befitting his skull-faced appearance. Jones’s Doom operates in plain sight, using his philosophical framework to justify horrific acts while maintaining complete control over his followers. One hides his true nature; the other makes his monstrosity part of his appeal.

What makes both versions equally compelling is that they serve as perfect foils to their respective heroes. Howard’s Doom challenges Kull’s physical prowess with otherworldly sorcery, forcing the warrior-king to confront threats beyond his understanding. Jones’s Doom, meanwhile, serves as both father figure and antagonist to Schwarzenegger’s Conan, creating a more complex psychological dynamic than a straightforward hero-villain relationship.

Modern fantasy has drawn from both interpretations. As Curley observes, “Just as Conan set the standard for barbarians throughout all of fantasy, Thulsa Doom has become the quintessential immortal wizard.” From Dungeons & Dragons liches to Skeletor and Voldemort, traces of both Dooms can be found throughout fantasy.

Contemporary comics have even attempted to reconcile these divergent portrayals. In “Conan the Barbarian: The Age Unconquered” (issues 9-12), writer Jim Zub brings Conan, Kull, and Brule together against a Thulsa Doom who combines elements from both versions. “It’s clearly the best of both worlds,” notes Curley. “Here we get a mix of that James Earl Jones Thulsa Doom and the classic Robert E. Howard version of the character.”

Despite the extreme divergence from Howard’s creation, both versions continue to influence fantasy storytelling in different but complementary ways. Howard’s skull-faced sorcerer established the template for what would become the lich – the undead wizard whose quest for immortality transforms them into something inhuman. This archetype continues to appear in countless fantasy stories, games, and films.

Meanwhile, Jones’s philosophical cult leader has influenced how compelling villains are written across all media. His ability to justify evil through twisted logic, to present monstrosity as enlightenment, can be seen in villains from Hannibal Lecter to Thanos. The “villain with a point” has become a staple of modern storytelling, and Jones’s Doom stands as one of its earliest and most effective examples.

Together, these two versions of Thulsa Doom represent different facets of effective villainy. One embodies the inhuman threat that cannot be reasoned with; the other represents the seductive logic of evil that can turn heroes’ own allies against them. Both are essential tools in storytellers’ arsenals.

As we continue to explore this character, both on screen and in literature, we can appreciate how these different interpretations don’t diminish one another, but instead create a more complex and fascinating whole.

After all, what better fate for a shape-shifting villain than to exist in multiple forms, each terrifying in its own unique way?

Want to dive deeper into the fascinating history of Thulsa Doom?

Check out Shawn Curley’s excellent video exploration of Thulsa Doom below!

Lo Terry

In his effort to help Heroic Signatures tell legendary stories, Lo Terry does a lot. Sometimes, that means spearheading an innovative, AI-driven tavern adventure. In others it means writing words in the voice of a mischievous merchant for people to chuckle at. It's a fun time.