By the late ’20s and early ’30s, social restrictions on women’s life choices were finally starting to loosen again. The Victorian straitjacket of housework and servitude was, if not slipping, then at least wearing thin. Writers, predominantly male, were still perfectly happy to continue reinforcing the old status quo however – that is, if it even occurred to them that there might be something to challenge.

Women writers were even less likely that their male counterparts to have their characters step clearly out of line, since they already faced a battle merely to have their work considered. C. L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry is the clear exception – she was the first writer openly influenced by Howard’s work, and Jirel the first female sword and sorcery protagonist. When he sent her a copy of his first Dark Agnes story, she was very enthusiastic.

Women were not, typically, the focus of Robert E. Howard’s tales. His earlier dramatic heroes, like Kull, Kane, and Mak Morn, were disinterested in sex – or, rather, too consumed with other, weightier matters to permit themselves any hint of self-indulgence. The comedic heroes, like Elkins, Costigan, and Dorgan, were lovelorn, desperately trying to win women’s interest but rarely getting anywhere.

Conan’s stories are, of course, a deliberate departure from these other patterns. As discussed earlier, Conan was invented precisely to appeal to the modern, ”civilized” nature that Howard despised. So the majority of the woman in the Cimmerian’s path are weak and pliant, just there as busty trophies for the taking and then discarding. There are a couple of notable exceptions, and we’ll get to them shortly. The rest, however, are best glossed over as fan service, a commercial decision that reflected only Howard’s disdain for civilization and its conventions.

But neither of these elements should be taken to indicate that Howard was in any way misogynistic. Quite the contrary. His strong, intelligent mother, and other important female influences in his early life, had instilled him with a deep respect for women that was highly unusual amongst the men of the time. Surviving letters show that he passionately defended women’s achievements to his friends. As an adult, he fought often with his father about how his mother was treated, and when he fell in love, it was with Novalyne Price, a vibrant, free-spirited writer and history teacher. If anything, Howard’s hesitation to write about women indicates an understanding of how the Pulp market demanded that they be treated, and a disinclination to lower himself to that level.

So when he permitted himself to write the women he believed in, Howard was as exuberant and electric as ever. His publishers weren’t particularly interested, so he didn’t get to spend much time with these characters, and we are the poorer for it. But his women are every bit as interesting as his men, and worth just as much attention. One, in particular, remains famous today – sort of, anyway.

Red Sonya

No, that’s not a typo. The pneumatic Red Sonja, of chainmail bikini and Brigitte Nielsen fame, was created in 1973 by Roy Thomas and Barry Smith to go into Marvel’s Conan comics. Boris Vallejo’s artistic genius helped ensure that her outfit became a cheesecake fantasy cliché. Red Sonja is very much a creation of her time, and if you want to know or see more, it’s all just a Google away. She owes very little to Howard, save her name and initial seed of inspiration.

Red Sonya of Rogatino, the one actually created by Robert E. Howard, is a very different person. She appears only in the story “The Shadow of the Vulture”, which was published in The Magic Carpet Magazine in the January 1934 edition. It’s not a work of fantasy – the story is a retelling of the siege of Vienna in 1529. Suleiman the Magnificent, sultan of the Ottoman empire, had extended his borders to take control of much of Hungary at the Battle of Mohács in 1526. The siege of Vienna was his attempt to absorb the rest of Hungary, and push west to pave the way for further expansion into Western Europe. It’s a great read, and it’s fascinating to get a look at one of the nexus points of western history. If the weather had been a little better that year, I might easily be writing in Turkish now, rather than English.

The main character of “The Shadow of the Vulture” is a fictional Austrian knight, an amiable drunkard named Gottfried Von Kalmbach who gets caught up in the siege. Red Sonya of Rogatino is one of the defenders, a ferocious and deadly Polish/Ukrainian swordswoman and pistoleer dressed in a steel cap, a shirt of chainmail, baggy trousers tucked into thigh-high leather boots, and a scarlet cloak. She’s described variously as tall, lithe, splendid, and supple, with shoulder-length red-gold hair, and when she first appears, she’s firing a cannon into a Turkish gun crew.

Gottfried quickly finds out that she’s the sister of the Sultan’s favourite harem girl, and that she loathes the both of them with abiding passion. She doesn’t go into detail, but between the lines, the implication is that she hates the Sultan for kidnapping and enslaving her sister, and her sister for becoming his enthusiastic companion. She’s proud, and disdainful of Von Kalmbach, but treats the men around her genially. They, in return, treat her as they would any other skilled comrade – an unusual one for sure, but all the more respected for that.

Despite being unimpressed by Gottfried, Sonya saves his life several times anyway over the course of the story, demonstrating her skill, courage, and cunning. Along the way, she accidentally spites him into leading a drunken sally against the invaders —one which ends up triggering the end of Suleiman’s siege. The story finishes with Gottfried and Sonya sending the sultan the severed head of his chief murderer, packed in herbs for freshness, along with an offensive little note. The implication is that they’ve become at least friends.

While Red Sonya’s name was slightly tweaked for the comics character, there’s little else of her in the Thomas and Smith creation. In fact, the ’73 barbarian owes considerably more of her inspiration to the most important of Howard’s warrior women: Dark Agnes.

Dark Agnes De Chastillon

Agnes de Chastillon was a French woman from a small village in Normandy called La Fere, the younger daughter of an aging former mercenary. Her father, a bastard son of the Duc de Chastillon, was a cruel and oppressive man who beat and verbally abused his children relentlessly. She hated him, but even so, she recognised that brutal years as a mercenary had warped him into the monster she knew. But there was no forgiveness in that understanding. Rather than fit into the unpleasant marriage and servitude he expected of her, she fled. The speed, resilience, strength and cunning she’d learned from dealing with her father’s abuses made her well-suited to combat, and she quickly became an expert swordswoman.

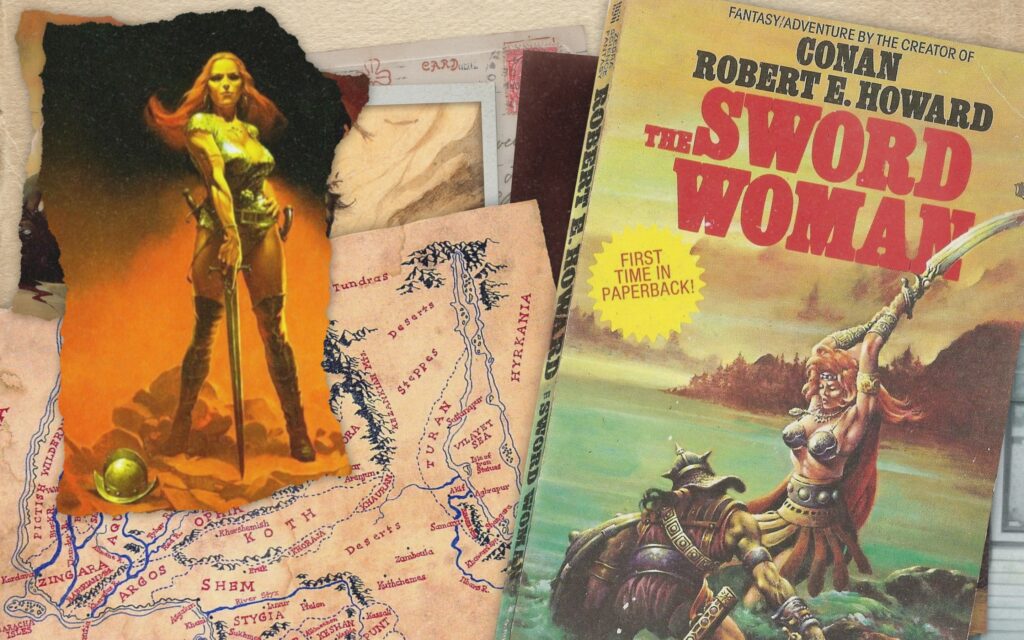

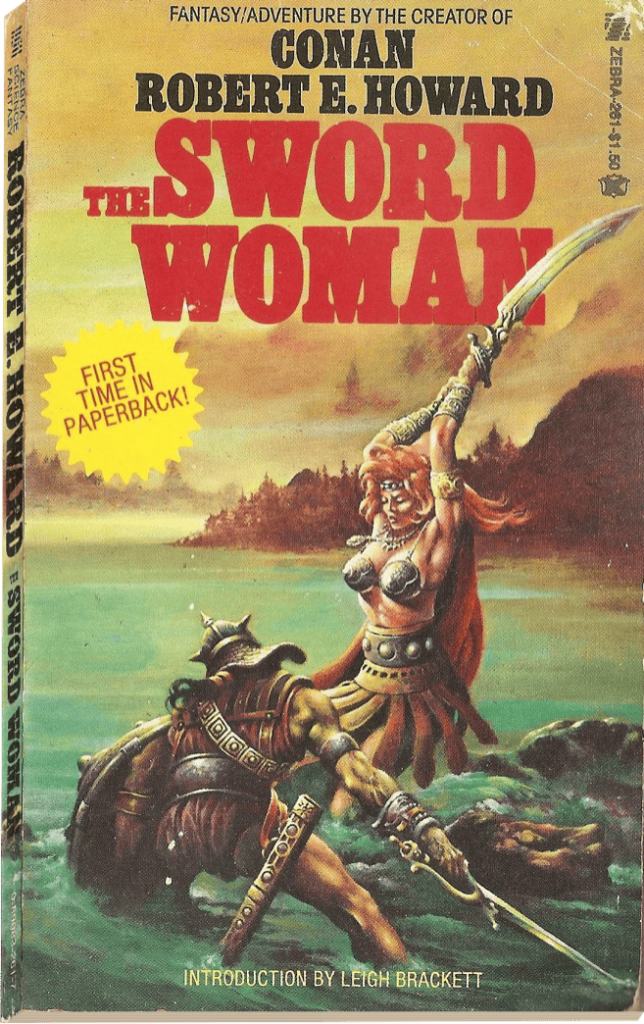

Robert E. Howard wrote two full stories about Dark Agnes de la Fere, “Sword Woman” and “Blades for France”, and left a third, “Mistress of Death” as incomplete drafts. The tales are set in 16th century France, told by Agnes in first person, and they describe fictional but plausible events and intrigues of the period, borrowing real historical figures as necessary.

The Dark Agnes stories are surprisingly modern in outlook, with an unflinching look at women’s expected roles and lives. Agnes is magnificently defiant about the whole thing, and proceeds to carve an entirely different reality for herself than the one the men around her inhabit. The writing is as good as any of Howard’s other work, but the Pulps were a broadly misogynistic market, and the stories weren’t published until 1975.

Readers should be aware that “Mistress of Death” was eventually completed in the ’70s by Gerald W. Page, who neutered Agnes into a far more typical female character of the time. She has to be rescued from death by her valiant manly companion repeatedly, and at the end of the story, the fellow even reassures her that there’s no shame in acting as a woman! Although Howard’s original fragments of “Mistress of Death” have very occasionally been published – most accessibly in Del Rey’s 2011 compilation Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures – the great majority of versions out there are the Page adaptation, which is best avoided.

“Sword Woman” opens on Agnes’s father describing her as the “red-haired spawn of the devil”, which is about as polite towards her as he ever gets on page. She’s in the forest, wearily gathering a back-straining heap of firewood, but it’s the day he has chosen for her wedding – a fact that she’s blanked out of her mind. He’s furious at having to come to get her, and gloats that his new son-in-law, Francois, will tame her with violence. She in turn is disgusted by her would-be husband, and utterly enraged at the notion of being tamed. When she tells her father she refuses to marry him, he beats her into unconsciousness – far from the first time this has occurred.

She comes round in their hut, dressed in her wedding clothes, too concussed and despairing to rip the hateful finery off. There are sounds of celebration outside, and her sister comes in, ostensibly to rouse her. Ysabel is just a few years older than Agnes, but she is gnarled and bent, her face lined with pain and exhaustion. She laments her brokenness, and although she tells her younger sister that this is the one day in her life when she is allowed to be joyful, that is not her real message. She swiftly takes a darker turn:

“Life is a hard thing for a woman. Your tall supple body will grow bent like mine, and broken with childbearing; your hands will become twisted — and your mind will grow strange and grey — with the toil and the weariness — and the everlasting face of a man you hate … look at me. Would you become as I?”

“Sword Woman”, Robert E. Howard

She gives Agnes a dagger, and tells her to take the only way out – suicide. It’s the first time Agnes has ever held a weapon, but the blade feels oddly familiar, and rather than kill herself, she hides it in her dress. The celebrants spill into the hut and forcibly drag her outside to greet her new husband. The sight of the loathsome fellow quells her struggles, and she’s pushed in front of him to be claimed and taken. In an instant, she pulls out the dagger, stabs Francois through the heart, and runs off. She escapes into the forest despite her father’s attempt to shoot her, and the villagers are too scared of the deep woods to pursue her far.

The next morning, Agnes wakes up on the forest floor, and the memory of the previous evening fills her with a wild delight, so that she wants to dance and sing. Instead, she cleans Francois’s blood off the dagger, and continues on her way. She finds a thin road through the forest, and has not been following it long when she hears an approaching horse. Her instincts warn her to hide, but then she realises that she’s not even a little scared. Instead she plants herself in the middle of the road defiantly, dagger in hand.

The horseman is expensively dressed but down at heel, and in his astonishment accuses her of being a forest-sprite or dawn goddess. He is startled into honestly introducing himself as one Etienne Villiers, formerly of Aquitaine, and after a little conversation, he offers to take her south to Chartres so she can find tavern work. Agnes points out her father will be pursuing her, so Villiers disguises her as a boy, mugging a lad he saw a few minutes earlier for his clothes.

They make their way through the forest, and around midday they come to a tavern, the Knaves’ Fingers. It’s an unpleasant place, with an unpleasant host and a guest whom Villiers appears to recognise, but he decides they’ll rest there, and takes a room so Agnes can get some sleep. He explains quietly that he doesn’t trust the innkeeper, and that they’ll move on after sunset.

She wakes up to find it dark outside, and someone fumbling around the room. When she calls out after Villiers, the intruder exits. Agnes follows, and sees the innkeeper running for the stables and dashing off on horseback. There’s no one awake in the tap-room, but in a small room to one side she hears Etienne negotiating her sale with the other guest, Thibault. She bursts in and slaughters Thibault before either man can react. Villiers mounts a desperate defence, and his armour prevents a killing blow, but she clubs him down with a broken table leg, beating him so badly that he can’t get up.

She’s going to leave him there to die until she realises that by calling his name earlier, she betrayed his real identity to the innkeeper, and that there is a huge bounty that has been placed on his head by the local Duke. Her hatred for the nobility outweighs her resentment at his betrayal, and she forces him onto his horse and they ride westward for a tavern that he tells her is run by a friend.

The innkeeper friend, Perducas, is bewildered and intimidated by Agnes and her frank statement that she’s the one who has brought Villiers to the edge of death. But he takes the man up to a good room, and the pair of them bind his wounds and set his broken bones. Etienne asks Agnes to stay while he heals, and she consents. Over the following week, she learns that he is being hunted because he used to work for the Duke, and knows details of certain treasons.

When a famous mercenary captain, Guiscard de Clisson, arrives at the inn, she asks for a place in his company. He tells her she’s being silly, and suggests she’d do better as his lover, provoking Agnes’s best-known enraged outburst:

“Ever the man in men!” I said between my teeth. “Let a woman know her proper place: let her milk and spin and sew and bake and bear children, not look beyond her threshold or the command of her lord and master! Bah! I spit on you all! There is no man alive who can face me with weapons and live, and before I die, I’ll prove it to the world. Women! Cows! Slaves! Whimpering, cringing serfs, crouching to blows, revenging themselves by — taking their own lives, as my sister urged me to do. Ha! You deny me a place among men? By God, I’ll live as I please and die as God wills, but if I’m not fit to be a man’s comrade, at least I’ll be no man’s mistress. So go ye to hell, Guiscard de Clisson, and may the devil tear your heart!”

“Sword Woman”, Robert E. Howard

She storms off, leaving Guiscard in absolute astonishment. Villiers is still recovering, and she gets him talking about why he’s such a wretch. During that conversation, five of Thibault’s comrades find him, determined to kill him because they believe he was the one who murdered their friend. Agnes tells them that she killed the man, but they dismiss her outright. They’re about to start torturing Etienne when she hacks the head off one of them, and uses a stolen pistol to execute another. The remaining trio attack her, and although she knows little of formal swordplay, she is ferociously aggressive and lightning-quick, and kills all three.

By the time Perducas the innkeeper arrives, with de Clisson hot on his heels, Agnes is standing by the window, sword in hand. She tells Villiers that her accidental betrayal is repaid, and as she’s about to leave, de Clisson offers her the position she asked for earlier.

They spend a further week at the tavern, while he outfits her as he deems appropriate for one of his band – clothing similar to that worn by Red Sonya of Rogatino, along with a good sword, two pistols, and a fine warhorse. Most of that time is spent training her with the weapons. Guiscard is the finest swordsman in France, and Agnes is a natural in the art, learning all manner of techniques and nasty tricks from him.

As they’re leaving, Etienne calls out from his bedroom window that she hasn’t even said goodbye. She responds that there is neither debt not friendship between them, and leaves. She and de Clisson have only gone a few miles before they spot a ruffian who slips into the woods at the sight of them. Agnes is certain an ambush is coming, but Guiscard discounts it. Hidden attackers fire on them, killing him and startling her horse into bolting. She is knocked out of her saddle, into bushes, her leg wounded.

The ambushers fetch their master, a captain named d’Valence, who is horrified that the dead man is de Clisson rather than Villiers. He declares that the duke will hang him if he learns of the error, for de Clisson was well-loved, and sends his ruffians out to find Agnes and make sure that she is indeed dead. They give chase, and she is brought to bay against a cliff, sheltering in a narrow cleft. She’s able to hold them off with her pistols, so they decide to wait for nightfall to rush her position. There’s no way out, but even with death assured, Agnes has no regret for her own end, only for that of Guiscard de Clisson.

As dusk falls, Etienne arrives at the top of the cliff with a knotted rope for her to climb. He explains that he heard the shooting, found de Clisson’s body, and knowing the area, searched along the cliff top until he found her. They are now both being hunted desperately, he by the Duke, and she by his captain, and as far as he’s concerned, she is wrong about the absence of debt – she saved his life. He offers her his comradeship, and they set off, one step ahead of d’Valence.

In the second, shorter story, “Blades for France”, Agnes and Etienne Villiers are attempting to negotiate an escape from France on the ship of an English pirate, Roger Hawksly. She’s heading to a rendezvous with Etienne when she’s accosted by – and slays – a thug in the forest. She takes his cloak and horse, along with the small amount of money he has, and a black silk mask she finds on him. It’s been a while since her last meal, so she stops at a tavern as evening is approaching. While she’s eating, a bravo sees her cloak and mistakes her for the man she’s just slain. He bids her mask up and follow him to their briefing.

There are ten of them in the secret meeting, all cloaked and black-masked, and the man who arrives to explain their mission is none other than Captain d’Valence. He fails to see through her disguise, and she rides off with the pack into the night. As Agnes gets her horse close, she overhears d’Valence talking to one of the men about Hawksly, but she doesn’t hesitate in driving her sword between his shoulder-blades. Then she turns to flee, even though she knows that his armour stopped her assassination attempt.

D’Valence does not pursue, and she makes it safely to her rendezvous with Etienne. He tells her that Hawksly’s ship has been secretly taken by English enemies, ones led by noblemen. He has no idea why any noble would attack a pirate secretly, but their escape from France is foiled. Then a rider approaches stealthily. Thinking it to be d’Valence, Agnes fires, and the horse is killed.

The rider, however, is a noblewoman, Francoise de Foix, the King’s chief mistress. She has been forced to betray an ally – Charles, Duc de Bourbon – to his enemies. Charles thinks he is meeting Francoise in a nearby inn, but instead d’Valence’s men will intercept him. She begs for Etienne and Agnes to help save him.

When the trio get to the Inn, they discover they are too late. A serving girl who hid during the attack says that d’Valence mentioned taking Charles to a ship. Etienne knows a short-cut to the only cove nearby, and they hurry there to find Hawksly’s ship in the bay, and d’Valence and his men on the beach, talking to some sailors from the ship who’ve used a smaller boat to come ashore.

D’Valence wants to see Hawksly in person, but the sailors refuse, and begin pulling Charles towards the boat. Realising that the sailor is an English lord, not a pirate, d’Valence attempts to kill Charles, to stop the English using him as a pawn against the King. A wild melee immediately ensues.

Agnes and Etienne charge in, and attempt to recover the prisoner. While d’Valence is desperately trying to kill Charles, he opens himself to Agnes’s attack. Once again his armour saves him. They duel for a time, but rather than fall to her blade, he flees the scene. Agnes manages to get to Charles before the English can take him, wounding their leader, Cardinal Wolsey, in the process.

While the English are distracted by Wolsey’s injury, Agnes and Etienne spirit Charles away to where Francoise is waiting. They give their horses to the nobles and send them fleeing off, leaving themselves in a slightly worse position than when they started the story.

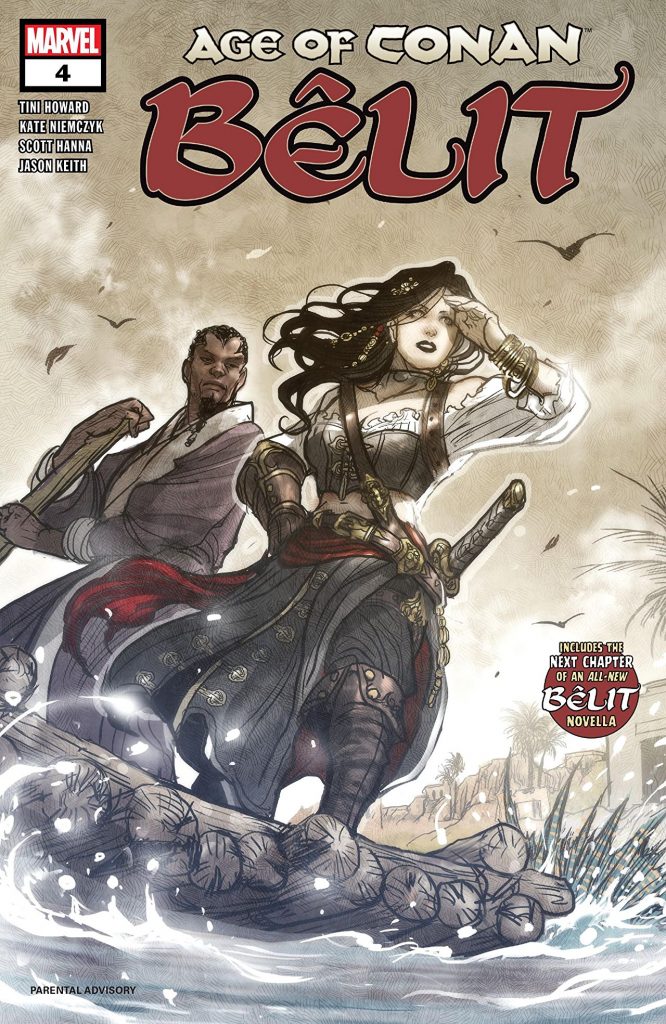

Bêlit

The most notable of Howard’s pirate queen characters, Bêlit is “the wildest she-devil unhanged”, the self-titled (and eponymous) Queen of the Black Coast in the 1934 Conan story of the same name. Although she wears only sandals, a red silk girdle, and some jewellery, her skin is as white as ivory. She is a beautiful Shemite woman of old royal stock, slim and lithe yet voluptuous, with dark, flashing eyes, red lips, and long black hair that cascades down her back.

During Conan’s first sea voyage, she attacks the ship he’s on, her pirates quickly overwhelming the crew. He jumps across to her ship, the Tigress, and starts demolishing opponents left and right. They pull back to riddle him with spears, but Bêlit intervenes. Instead, she offers him the opportunity to become her lover and partner. Conan is as enchanted with her looks and fierceness as she is with his, and the couple become a force of terror feared up and down the coast. She becomes his first and greatest love, an adoration that she matches. During their time together, Conan becomes an expert pirate.

Eventually, she gets wind of a fabled city up a supposedly cursed river, and they go to try to find and raid it. Instead, they find an ancient temple with a rich treasure of jewels, and a winged ape-monster. Conan encourages her to leave, but despite her love for him, her greed overpowers her. She raids the temple, grabbing a fortune in gems, and in particular a magnificent jewelled necklace. But the necklace is cursed, and she becomes erratic.

At the same time as they’re stealing the treasure, the ape-monster smashes the Tigress’s water casks, and it bedevils them over the days that follow. As the crew dwindles, the ape-monster toys with the ship, eventually hanging Bêlit by her necklace once it has killed all her crew.

Conan finally revenges himself on the monster, but only with the help of her soul, which returns from the grave in his instant of direst need. With the beast vanquished, Conan places Bêlit on a bier on the deck of the Tigress, surrounded by her treasures, and fires the ship, sending it off to a burning burial at sea.

Valeria of the red brotherhood

“Red Nails” was the last Conan story that Howard wrote. Weird Tales was being very slow in paying him at that point, and much as he hated having to think it, he was seriously considering the possibility that it might be his last ever work of fantasy. Determined to say what he meant, he turned the story into a requiem for the idea of civilisation, a final statement about the inevitable corruption that always came. It’s amongst the very best of the Conan stories, and remains deeply resonant today.

Valeria is an Aquilonian, lithe, supple, strong-limbed, and buxom, with long, golden hair tied back with red satin. She wears a shirt, silk sash, breeches, and flaring boots of soft leather. More importantly, she’s a seasoned adventurer and an expert fighter, someone even Conan views with wary respect.

Much of the story is told from Valeria’s viewpoint. She’s a respected pirate and an ongoing acquaintance of Conan’s. The pair have recently fled from the army that they’d been working for, Valeria because she killed an officer who was attempting to rape her, with Conan following, because he admired both her beauty and her spirit. Along the way, they find a long-lost city on a monster-filled plain. The current inhabitants are not numerous, and they welcome Conan and Valeria in.

After some discussion, the residents offer the newcomers heaps of treasure to help them defeat the monsters on the plains. The creatures – plainly dinosaurs, not that any of the characters know the term – have kept the folk penned in the city for more than fifty years, and they are desperate to be rid of them.

But there is, inevitably, treachery afoot. One of the city’s rulers is an ageless sorceress, and she seeks to consume Valeria’s soul in order to feed her own youthfulness. Her husband, unheeding of her plans, tries to rape Valeria, but is stopped and imprisoned by his wife for his pains. Conan frees him, and is then forced to kill him in self-defence. By the time it is all over, Valeria and Conan are the only living people in the whole city. They set off together for the coast, to find a ship and resume their piratical endeavours.

Valeria’s name was borrowed for a character in the 1982 John Milius film Conan the Barbarian. There was more of Bêlit in the movie character than of Valeria though, and her outfits tended towards the glittering and skimpy.

Honourable mentions

The line between Howard’s women heroes and his incidental female characters is not hard and fast. Plenty of them were skilled, brave, and independent. Both the Caribbean pirate Helen Tavrel (“The Isle of Pirates’ Doom”) and the Celtic princess Helen of Briton (“Tigers of the Sea”) are well worth consideration. Zenobia, Conan’s queen during his rule of Aquilonia, is definitely of interest, as are Yasmina, the Devi of Vendhya, in “The People of the Black Circle”, and Glory McGraw (A Gent from Bear Creek). Time and space are limited, unfortunately.

It’s easy to look at the Pulps in general, the Conan stories – and their illustrations – in particular, and at what the ’70s did to Howard’s work, and to decide that the man was a towering misogynist. It’s an entirely reasonable conclusion. It’s also utterly wrong. He loathed the restrictions that civilisation placed on women as much as the fetters he felt himself bound by. Indeed, his continued existence in a world he despised was nothing less than an act of devotion to his mother. If his work sometimes suggested otherwise, that is the reflection of the commercial environment he was in rather than of any convictions on his part.

Robert E. Howard undoubtedly had many flaws, but sexism was not one of them.

Look for the next installment in the Life and Times of Robert E. Howard series in a couple of weeks.

Tim Dedopulos

Tim is an author, publisher, and game designer with tons of experience. He’s writing the Life and Times of Robert E. Howard series for Conan.com.