Robert E. Howard was deeply sceptical about the supposed benefits of civilisation. As his work so clearly demonstrated, he longed for a world where honour, bravery, and martial strength were the primary virtues. He saw virtue as something to be enforced through physical might, and legislation as a shield for the corrupt to cower behind even as they abused the populace. Civilisation, in particular, was a smothering death of poisonous red tape, a tool for the contemptible to wield power over the decent. It made people soft and cynical, and cut them off from their true heritage. Instead of clean struggle, it offered de facto enslavement, meaningless busywork, and endless opportunities for vice and deceit. The worst politicians were smirking monsters selling the souls of the people they claimed to represent, and the best were not much of an improvement.

It was a stark but romanticised view of the world, and even if the twenty-first century is apparently bearing out some of his fears, the truth is that the mighty are rarely virtuous. Honour has very little effect on one’s ability to cut another man down where he stands. Looking at the world that Howard grew up in however, it’s not hard to see the patterns that helped shaped him to that opinion.

Howard, born in 1906, never got to experience the rough and tumble frontier that Texas had been in the late 19th century. The oil boom of the early 20th century totally reshaped the state, and much of the rest of the United States. But there were many aging men around him who had been there, and who recalled those violent times with a rosy nostalgia that turned a savage period into one of righteous adventure. Recollection has a way of editing out guilt and misdeed, and painting what remains as something to be looked back on fondly. The corollary to every yarn about the good old frontier days, of course, was that those times were gone, swept away on a tide of oil-money and new, ‘civilised’ settlement.

That second-hand resentment alone would have been enough to bias Howard against the new order. There was plenty of unpleasantness to observe first-hand, however. The oil boom brought a tide of money, and inevitably crime flooded in behind it. Corruption was the most genteel edge, but it extended through illegal vices to robbery, murder, and even flat-out banditry. As a young man, Howard got to see peers of his drawn into the darkness that came with the oil and its industry, there to spiral swiftly downwards.

The steady stream of broken bodies coming into his father’s medical practice helped emphasise how dysfunctional and dangerous the state was becoming. Some jobs inevitably take a toll on worldview, because of the way they necessarily attract certain experiences. Just as a police officer sees a disproportionately high amount of crime and meets far more criminals than almost anyone else, so the son of a travelling doctor is exposed to far more victims of violence and negligence than would otherwise be the case. It becomes very easy, in that environment, to assume that this is just how the world is.

When all you see are edge cases, you come to believe that the edge is everyone else’s normal too.

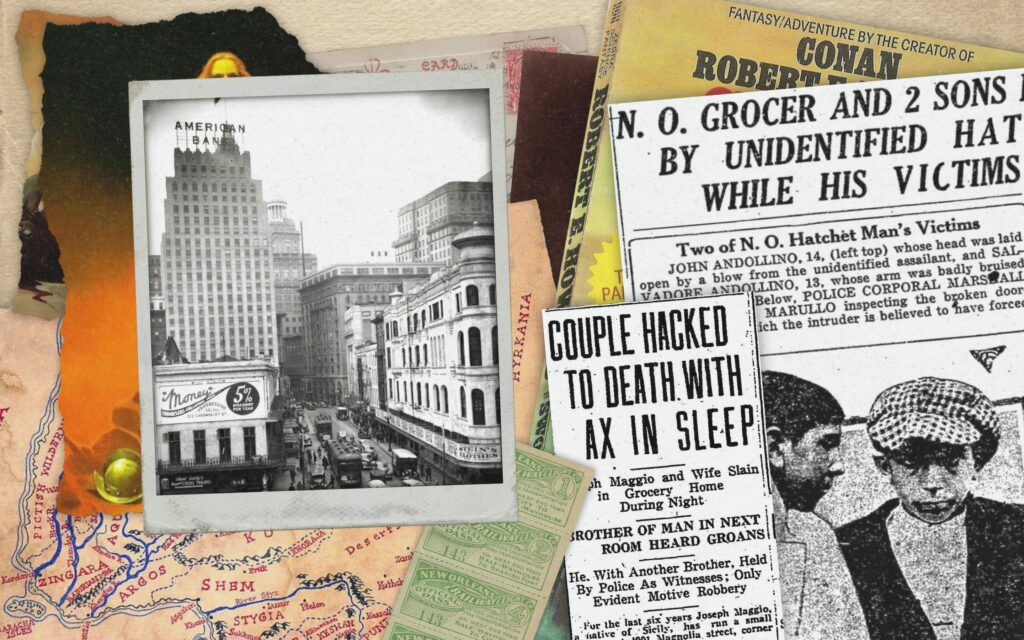

In early 1919, the Howard family was without a permanent base. As he often had before, Isaac Howard travelled around Texas, taking his medical services to places where he might be needed. He was in the process of setting up a long-term home in Cross Plains, but had not yet taken occupancy. In March of that year, he took the family to New Orleans, where he had arranged to take a seven-week medical course.

Amongst scholars of Howard’s work, that trip is famed for being the boy’s first exposure to the Picts. He came across the early Celtic tribe – who lived in what is now eastern and northern Scotland and who inspired so much of his fiction – in a library in Canal Street. He was immediately enthralled. That visit could also have been a chance to see another side of civilisation, to experience a grand, beautiful old city with a rich, vibrant life and deep roots into multiple ethnic communities. Perhaps, if he’d had a good time there, his deep revulsion for civilisation might have been softened a little.

Unfortunately, it was not to be. Instead of witnessing a more conducive version of society, Howard got to experience the Big Easy in the heights of a desperate, lurid panic over its most notorious serial killer – the Axeman of New Orleans.

The Axeman came to public attention in 1918. Researchers disagree about when the Axeman started his murders. There are killings going back to 1911 and 1912 that might possibly be his work, but opinion is strongly divided, as is often the case with unresolved serial murders. There is similar disagreement about the end of his killings. But there is a core period that is identifiably the work of one lunatic, starting in May 1918 and lasting some seventeen months. Some researchers have suggested that the Axeman abandoned New Orleans to continue elsewhere in Louisiana, but if so, his exploits fell off the public radar and are not now associated with him.

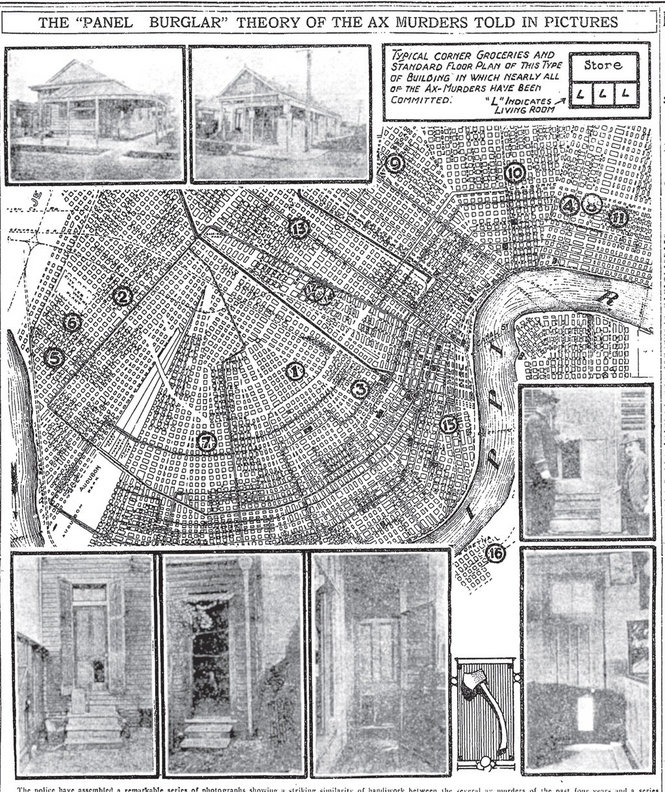

The Axeman killings targeted mostly Italians and Italian-Americans, with a preference for grocers, a trade that was dominated in the city by immigrant Italians and their families. The killer’s typical modus operandi was to steal an axe from his target and to use it in his attack, although sometimes the killing blow was dealt with a straight razor. The victims were not robbed or sexually despoiled, and many theorists have suggested underlying racial hatred as the primary motive. It’s also possible that some or all of the killings were related to Sicilian gang activity, an early iteration of the Mafia, but there’s no way to know for sure – the killer was never caught, and despite plenty of theorising as to his identity, the murders remain unsolved.

The first agreed victims of the Axeman were Joseph and Catherine Maggio. The Maggios were Italian grocers who lived on the premises at the corner of Magnolia Street and Upperline Street. Joseph’s brother, Andrew, was a barber, and lived next door. On the 22nd of May, 1918, Joseph and Catherine were at home sleeping when the Axeman broke in, slit their throats with a straight razor, and then laid their heads open with an axe. He then changed into a clean set of clothes and departed, ignoring money and other valuables that had been left out in plain sight. Catherine’s throat had been so deeply cut that her head was almost completely severed, but Joseph survived just long enough for his brother to hear horrible groaning through the wall and come to investigate.

Police found the Axeman’s clothes at the scene, and the razor was later recovered from a neighbouring garden. It turned out that the razor was from Andrew’s barber shop, having been brought home a couple of days earlier to have some nicks sharpened out. Police were suspicious of Andrew, and maintained that he ought to have heard the Axeman breaking in to his brother’s apartment, but the barber had been out drinking heavily that night as he was about to leave New Orleans and join the navy. Despite their best efforts, Andrew just wasn’t a fit for the crime, and his lack of potential motive and his accounts of having noticed an unfamiliar fellow hanging around near the grocery previously helped to shed further doubt on his potential guilt.

The next attack was on June 27th. Louis Besumer, who lived behind his grocery on the corner of Dorgenois and Laharp, was asleep with his mistress Harriet Lowe. Both were attacked with an axe, Besumer above his right temple, and Lowe above her right ear. The couple were found unconscious in a pool of blood early that morning by a driver, John Zanca, who was there to make a regular delivery for a bakery. The axe had been taken from the grocery, and was abandoned in the bathroom. Both survived the initial attack, and Besumer told police that he had been sleeping when the assault happened.

Lowe was badly affected by the attack, suffering cognitive difficulties and partial facial paralysis. She initially claimed to have been attacked by a mixed-race man, and despite the complete absence of any evidence, the police were quick to arrest Besumer’s new shop assistant, a 41-yr old African American named Lewis Oubicon, on the basis that he’d been contradictory about his location that morning. He was blatantly innocent, and when he was eventually released, focus turned to Besumer himself, who was discovered to be in the possession of several German, Russian, and Yiddish-language letters. Lowe, who was then going in and out of consciousness, denounced Besumer as a German spy, and he was immediately arrested.

Just two days later, the police released Besumer, and two of the lead investigators on the case were demoted for unacceptably poor work. But the idea of a spy had grabbed headlines and public attention, and Lowe herself went on to call up a storm of media interest with a series of wild and scandalous statements, including denunciations of the New Orleans police chief. When the papers realised she was Besumer’s mistress, and then his actual wife arrived from Ohio, she became the hottest news in the city.

Despite all of this, she returned home to Besumer but in August, after a failed surgery to correct her paralysis, she accused him of being her attacker. She died shortly afterwards, on August 5th, and Besumer was again arrested. This time he would spend nine months in jail, only to be fully acquitted in May 1919 after just ten minutes of jury deliberation.

The frenzy surrounding Lowe and Besumer had been great for the New Orleans newspapers, so the public were very well-primed for anything linking to the case.

On the morning of the day Lowe died, August 5th, a heavily pregnant woman named Anna Schneider was attacked by a ‘dark figure’ who accosted her in bed and bashed her repeatedly in the face with the base of a nearby lamp. She survived the attack, and was discovered some time after midnight by her husband Ed, who was late home from work. Her scalp was gashed, and her face was a mask of blood. Six dollars had been stolen from Ed’s wallet, but otherwise nothing was taken. There was no sign that either the window or the door had been forced, but Mrs. Schneider remembered little of the attack. Two days later, she gave birth to a healthy daughter.

Police were quick to arrest a man named James Gleason for the attack, primarily because he ran away from officers when approached. There was absolutely no evidence or any other reason to associate Gleason with the crime, and he attested that he’d fled simply because he’d been arrested so frequently in the past. He was released, and the police department began to openly suggest that the attack on Schneider might be linked to the attacks on Besumer, Lowe, and the Maggios.

The next attack came swiftly. The victim was Joseph Romano, an old man. Romano lived with his nieces, Pauline and Mary Bruno, and they were woken by a loud commotion during the night on August 10th, five days after the attack on Schneider and the death of Lowe. Romano was in the next room, and when Pauline and Mary rushed in there, they saw a heavy, dark-skinned man in a dark suit and hat running away. The old man had serious open wounds in his head, and though he was alive, and even able to walk to the ambulance under his own power, he succumbed to his injuries two days later.

Investigating the scene, police discovered that the house had been carefully ransacked, but nothing had been stolen. The murder weapon, a bloody axe, was found in the back yard. The Axeman had chiselled a panel off the back door in order to give himself a quiet entry.

In short order, the city had been bombarded with Harriet Lowe’s death, Louis Besumer’s second arrest, the attack on Anna Schneider, and police theories that there was a serial killer on the loose. So the murder of an old man by an axe-wielding maniac cunning enough to stealthily creep into his home threw New Orleans into flat-out panic. The Axeman completely dominated public thought, conversation, and action. People were scared and irrational, and the city quickly became chaotic. The police struggled under scores of reports of wild-looking axemen supposedly lurking in neighbourhoods and behind bushes all over the city. A bunch of people even reported finding axes in their back yards.

A retired Italian police detective named John Dantonio stepped forward to add fuel to the fire. He told press that he believed the Axeman had killed several people in 1911, and described similarities in the current and former cases to support his theories. In interviews, he characterised the Axeman as suffering from multiple personalities, turning him into a hidden monster who slew without reason when the urge came over him, but spent the rest of the time as a perfectly normal, pleasant, individual. Absolutely any innocuous fellow might be the serial killer. He might not even know himself to be the murderer. The idea swiftly inflamed the public’s already-rampant paranoia.

With local terror at a fever-pitch, and four murders in as many months under his belt, the Axeman vanished. Months passed, and while the killer remained near the front of people’s minds, the panic and chaos eased up. Howard, just 13, arrived with his parents for his seven-week stay early in March, 1919.

On March 10th, the Axeman struck again. Charles and Rosie Cortimiglia and their two-year-old daughter Mary lived on the corner of Second Street and Jefferson Avenue in the New Orleans suburb of Gretna. An aging neighbour across the street, Iorlando Jordano, came over to investigate and discovered that the home had been attacked. Mary was dead, and both Charles and Rosie were gravely injured with head wounds and skull fractures. When police examined the home, they discovered a panel had been carefully chiselled off the back door to permit entrance, and a bloody axe had been left on the back porch.

Charles Cortimiglia was able to leave Charity Hospital after a couple of days, but his wife had to stay there for significantly longer. The police were desperate to solve the crime swiftly, and Sheriff Louis Marrero and Chief Peter Leson decided that Iorlando Jordano and his teenage son, Frank, were the culprits. The Jordanos and the Cortimiglias were competing grocers, and some time previously, the Jordanos had actually taken the Cortimiglias to court over a dispute. That was enough, even though Iorlando was sixty-nine and too frail to have attacked anyone, and Frank, eighteen, weighed over two hundred pounds and could not possibly have squeezed through the chiselled panel on the door.

The police harangued the Cortimiglias continually while they were in the hospital, insisting that Frank had to be the killer. Charles loudly and repeatedly refused the police claims, both then and later, to reporters. But then he was only trapped in the hospital with them for a couple of days. Rosie was there for significantly longer. Despite her constant protestations that she didn’t know, she was arrested as soon as she was discharged from hospital and stuck in Gretna jail. She was only released when she agreed to sign an affidavit saying her daughter had been murdered by her neighbours.

Iorlando and Frank were arrested, put through a swift trial, and even though the only evidence was Rosie’s affidavit – attested as unreliable by her doctor – they were found guilty. Iorlando was sentenced to life, and Frank slated to hang. Shortly after the ludicrous trial, Charles divorced Rosie.

Nine months later, Rosie went to the Times-Picayune newsrooms and gave them an affidavit that she’d never seen her attacker, and she’d been forced by the police to make her accusation. She was telling the truth now because St. Joseph had visited her in a dream to tell her to do so. Despite this, the prosecution refused to drop the charges, and even threatened her with charges if she didn’t recant. This time, however, she refused. Eventually, Frank and Iorlando’s sentences were overturned, and the father and son would be released in December of 1920.

The news of the Axeman’s return sent New Orleans into a tailspin. Newspaper and magazine front pages were filled with gleefully lurid drawings of the scene that Iorlando had discovered – Rosie standing in her bedroom doorway drenched in blood, holding the corpse of her infant child, with her husband splayed out at her feet. The image seared itself into Robert’s subconscious. The panic and chaos of the previous year was violently reawakened, parents across the city terrorised by the idea that the maniac was coming for their baby next.

Just a few days later, on March 14th 1919, the city suffered an even worse blow to its collective sanity – a letter from the Axeman, printed in full by the Times-Picayune, threatening further slaughter. It’s an interesting read, for several reasons:

Hell, March 13, 1919

Esteemed Mortal:

They have never caught me and they never will. They have never seen me, for I am invisible, even as the ether that surrounds your earth. I am not a human being, but a spirit and a demon from the hottest hell. I am what you Orleanians and your foolish police call the Axeman.

When I see fit, I shall come and claim other victims. I alone know whom they shall be. I shall leave no clue except my bloody axe, besmeared with blood and brains of he whom I have sent below to keep me company.

If you wish you may tell the police to be careful not to rile me. Of course, I am a reasonable spirit. I take no offense at the way they have conducted their investigations in the past. In fact, they have been so utterly stupid as to not only amuse me, but His Satanic Majesty, Francis Josef, etc. But tell them to beware. Let them not try to discover what I am, for it was better that they were never born than to incur the wrath of the Axeman. I don’t think there is any need of such a warning, for I feel sure the police will always dodge me, as they have in the past. They are wise and know how to keep away from all harm.

Undoubtedly, you Orleanians think of me as a most horrible murderer, which I am, but I could be much worse if I wanted to. If I wished, I could pay a visit to your city every night. At will, I could slay thousands of your best citizens, for I am in close relationship with the Angel of Death.

Now, to be exact, at 12:15 (earthly time) on next Tuesday night [March 19, 1919], I am going to pass over New Orleans. In my infinite mercy, I am going to make a little proposition to you people. Here it is:

I am very fond of jazz music, and I swear by all the devils in the nether regions that every person shall be spared in whose home a jazz band is in full swing at the time I have just mentioned. If everyone has a jazz band going, well, then, so much the better for you people. One thing is certain and that is that some of your people who do not jazz it on Tuesday night (if there be any) will get the axe.

Well, as I am cold and crave the warmth of my native Tartarus, and it is about time I leave your earthly home, I will cease my discourse. Hoping that thou wilt publish this, that it may go well with thee, I have been, am and will be the worst spirit that ever existed either in fact or realm of fancy.

– The Axeman

New Orleans took the Axeman’s threat seriously, and March 19th was a night of frantic music. Dance halls, bars, and any other venue that could fit a jazz band had done so, and they were all packed to the rafters. Others threw jazz parties, mopping up every professional, amateur, and even half-skilled jazz enthusiast available, while the rest of the city crowded around phonographs to play jazz records. No-one was killed that night, but that didn’t stop people carrying around shotguns again the next day, or returning to shifts for all-night watch over their homes. The Howard family left the city a little over a month later, with the city still reeling from the letter, the Cortimiglia attack, and the police’s blatant railroading of the following investigation.

Howard carried the Axeman with him when he left, buried deep in his unconscious, to rise up and bedevil him in nightmares. He was prone to sleepwalking and other sleep disturbances, and woke up in the middle of swinging a punch often enough that he started tying his right hand to his bed. One night, while staying with Clyde Smith in Brownwood, he screamed wildly enough to wake the whole house in panic, and then leapt out of a window, all as part of a nightmare struggle. Smith had standing instructions on how to talk Howard down from a sleepwalk episode, and did so. Later, once he’d properly woken up, he told Smith he’d seen a dream headline stating “Axe Murderer Slays Three”.

Howard’s 1934 story The Pigeons From Hell contains imagery strongly suggestive of the Axeman murders – a horribly-wounded man shuffling away from the scene of an attack, his skull laid open with an axe. It’s not hard to see potential influences from the killings spread across the rest of his work though, from the gory news reports to the gleeful letter and even the blatant official corruption. New Orleans taught him a unpleasant lesson that remained with him for the rest of his life.

The Axeman continued after the Howard family’s departure. Grocer Steve Boca was attacked on August 10th, 1919, a panel chiselled from his door, and an axe left behind. He survived the attack, but couldn’t later remember any details. William Carson, a drug-store owner, managed to use his gun to drive an intruder off on September 2nd, and discovered that the man had left an axe behind. The following night, September 3rd, Sarah Laumann was attacked, her assailant gaining entrance through a window and leaving a bloody axe in the yard. Despite severe head and mouth injuries, she survived, although she didn’t remember any details. Mike Pepitone was not so lucky. On October 27th, his wife discovered him dead in their bedroom, and a large, axe-wielding man running away.

There were some later attacks too that might possibly have been the Axeman – Joseph Spero and his daughter in December 1920, in the city of Alexandria in central Louisiana, Giovanni Orlando of DeRiddler in western Louisiana a month later, in January 1921, and Frank Scalisi of nearby Lake Charles in April of the same year. Opinion is divided on whether these later attacks were the work of the Axeman or not. Some researchers do not even attribute the Pepitone murder to him.

We’re very unlikely to ever know for sure. The Axeman was never caught, and there are a number of potential suspects, all of whom are problematic in one way or another. There’s no evidence that Robert E. Howard even attempted to keep up with the case after his escape from New Orleans. But then, he hardly would have needed to.

The Axeman had already done him more than enough damage.

Look for the next installment in the Life and Times of Robert E. Howard series in a couple of weeks.

Tim Dedopulos

Tim is an author, publisher, and game designer with tons of experience. He’s writing the Life and Times of Robert E. Howard series for Conan.com.