Robert E. Howard, the creator of Conan the Barbarian, remains one of the most important literary figures in American fantasy. His influence has been as strong, as profound, as any contribution made by J.R.R. Tolkien or Lewis Carroll. Unlike those genteel British authors however, his work was a product of a very different environment – the corrupt, violent world of the Texan Oil-Boom.

The pulp magazines were born out of the Victorian penny dreadfuls and dime-novels, printed in huge volumes on the cheapest possible paper, and packed with lurid, exciting stories of all imaginable sorts. As printing technology got better the pulps lost ground, and modern comics took their place. At their height however, in the thirties, some of the pulps were selling a million copies an issue. The pulps were the perfect home for Howard’s bloody, action-packed tales, and he became hugely popular. Had he lived longer, he would have seen his work move outside them, but he took his own life as his first novel was nearing publication.

In just thirty years, he managed to write more than four hundred stories and five hundred poems. Many of them were published in his lifetime, enough to provide him with a very solid living. In addition to the genres he created himself, Sword and Sorcery and Weird West, Howard wrote substantially in the genres of boxing, westerns, horror, mythic/romantic history, adventure, comedy, mystery, and even some mild erotica. His legacy has been the most profound within fantasy however, and that is where he is best-remembered.

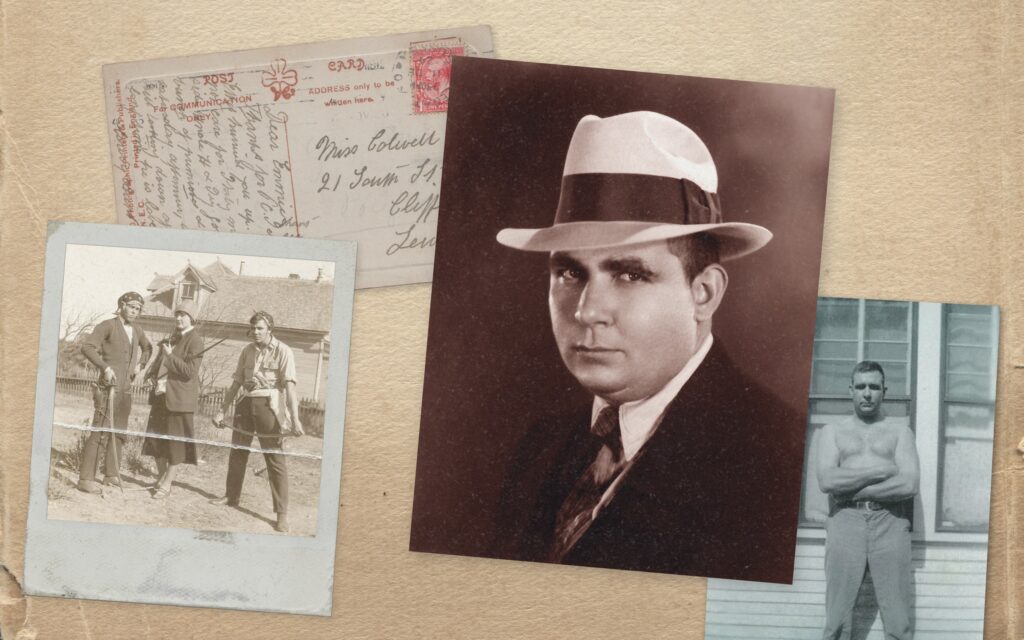

Robert Ervin Howard was born on January 22, 1906 in the tiny Texas community of Peaster to Isaac and Hester Howard. Isaac was a country doctor, and the family moved regularly from town to town providing medical services to places in need of a healer. The oil-boom had begun in earnest in 1901, and the Howards travelled around in its wake, going to a succession of boom towns, cattle towns, and other places where growth was suddenly exceeding the established capacities.

This world had a profound effect on the young child. As the son of a doctor, he had constant exposure to physical trauma. Horrible accidents and injuries were disturbingly common in the new, voraciously unregulated industry, but so were violence and murder. Besides, while the American Frontier period was already passing into myth, there were lots of older folks around who’d lived through it, and the towns were steeped in bloody stories of gunfights, native raids, crime sprees and murders. There were also plenty of former slaves with their own stories to tell of lynchings and abuses, and with myths and legends passed down from their hereditary cultures.

Howard grew up steeped in a thick, ugly brew of violence, hatred and corruption from the very beginning. The boom towns he lived in were dangerous places, filled with swaggering bullies and drunks, and precious few policemen around to rein them in. Naturally, there were lots of savage predators swarming around these roughnecks, ready to part them from their impressive earnings. There was very little justice to be seen. Being in this environment at a young age had a deep effect.

There was another side to the violence, though. Boxing was far and away the most popular sport in the nation during this period, and Howard was fascinated with it. He was particularly drawn to the ‘iron men’ – boxers of no particular skill or grace whose incredible resilience made them very effective competitors. This astonishing stamina would go on to become a key characteristic of his heroes, and he came to consider violent contest as one of the most important pursuits available to a man.

Hester Howard was an educated woman with a deep love of books and poetry, and she did her best to temper her son’s world. She read books and poems with him every day, taught him to be curious about history, and did everything she could to encourage him in his writing. She was generous with her family to a fault. During her youth, she’d spent extended periods of time caring for various sickly family members. Sadly, as a consequence she caught tuberculosis, and she was already unwell when Howard was born. From her, he developed a deep love of poetry, writing, and history, but he also internalised the unintended lesson that virtue brought only punishment, because the world was cruel, random, and pointless.

These influences combined over the course of Howard’s childhood to leave him with a deep, bedrock-layer distrust of civilisation. Progress meant debauchery and crime, and the more society progressed, the nastier it became until it would, inevitably, collapse under the weight of its own unpleasantness. Purity lay in simpler times, with the rule of virtuous masculinity as embodied by strength and a simplicity that was the enemy of devious, morally-compromised sophistication.

Howard’s first formal schooling was in 1914, in the town of Bagwell. He was eight. It took very little time for him to find the atmosphere confining. His memory was superb, possibly even fully eidetic, and so he spent most of his time extremely bored. Fitting in to the school world at the time meant roughhousing and play-fighting, but his mother did not approve, and stopped him at every turn. Resentful classmates quickly turned into enthusiastic bullies, which helped to reinforce the nihilistic feelings that he was already developing, and heighten his distaste for the modern world. He was writing bloody battle stories of Vikings and Arab warriors by the age of nine, and reading extensively – myth, legend, history, adventure tales of the east, stories of reincarnation and past life memories, anything with some wonder and excitement.

The family continued to move around, finally settling in the small, quiet town of Cross Plains in 1919. Isaac bought a house, and had it fitted with all the modern conveniences like electricity, plumbing, and gas. Later that year, he went to New Orleans to take some medical courses, and the family went with him. During that visit, Howard found a rather fanciful book on British history at a Canal Street library, and first encountered the Picts – the warlike inhabitants of northern and eastern Scotland who daubed themselves in woad and gave the Romans such a hard time. There were portrayed as ignorant, savage barbarians, outsiders who viewed society with great scepticism. While they lived lives of gruelling hardship though, they possessed true freedom and a vibrant sense of defiance. They captured the boy’s imagination, becoming a symbol of what the world had once been, and had now lost.

The following year, to fourteen-year-old Howard’s horror, an oil gusher was discovered within Cross Plains, and it instantly became a boom-town. Money poured in, along with a horde of rough, hard-bitten workers. Vice and organised crime came with them, flooding everything. Suddenly the streets were filled with swaggering bullies and supercilious oil barons, corrupt lawyers and councillors, gangsters and prostitutes, drugs, gambling, and even outright banditry. The population grew almost tenfold in nearly no time at all, and Howard saw his peers dissolving into this toxic new environment. If there had ever been a chance of him softening his opinion of society, it died there.

He turned away from the world, and dove enthusiastically into the pulps. Now fifteen, he started writing prolifically, submitting his work to any pulp he thought it might fit with. He created a slew of western and romantic historical characters that would go on to eventually find publication – Solomon Kane, Bran Mak Morn, El Borak, The Sonora Kid – but only got a growing stack of rejection slips. Undeterred, he started studying the pulps rather than just reading them, observing the style and tone of the various publications, and working to match pieces to specific outlets.

Publication finally came the following year, albeit unpaid. He was with his mother in lodgings in Brownwood, a nearby city, in order to attend his final year of high school. He made his first true friends here, other boys who loved not only sports, but also writing, history, and poetry. The school paper was called The Tattler, and in December 1922, it published two of his stories that had won prizes in small competitions.

In 1923, aged 17, he went home to Cross Plains. He regularly exchanged long letters with his Brownwood friends, and created for himself a daily exercise routine to start building up muscle. This included chopping up logs, punching a filled grain sack, lifting weights, and doing jumps. He kept at it, and slowly became quite muscular. At the same time, he was working odd jobs that he universally loathed. These included collecting garbage, picking cotton in the fields, serving sodas, helping out in a grocery store, and a number of other menial, tiring, poorly-paid things.

He returned to Brownwood in 1924 to do a course in stenography at Howard Payne Business College. He was lodging with a friend this time, and although the stipend his parents permitted him left him perpetually broke, he had a decent time. Over the Thanksgiving week that year, he finally received his first professional acceptance – Weird Tales agreed to publish the story “Spear and Fang”, which was about a Cro-Magnon man fighting against a Neanderthal, with a beautiful woman as the prize. He finished his stenography training, and rather than continue with business school, returned home to devote himself to becoming a full-time writer.

A second story acceptance from Weird Tales came just a few weeks later. Howard found work with the local newspaper, the Cross Plains Review, writing columns about the local oil industry. Over the next year or so, he lost the job at the newspaper, then gained and lost jobs at the post office, the gas company, an oil company, and other places besides. He was not temperamentally suited to being told what to do, and although he had no fear of hard work, he loathed being taken advantage of.

Story sales continued, sporadic but frequent enough to keep him dedicated, and he became a regular contributor to Weird Tales. When he was 20, he got his first cover story with “Wolfshead”, a werewolf piece that Weird Tales were particularly happy with. He was working pulling sodas at the time, and although the pay was fair for once, the hours were absolutely gruelling. An oil-worker buddy suggested he try some amateur boxing as a way of unwinding. He loved it. Boxing immediately joined his writing as another important source of catharsis for his anger and frustration.

That summer, exhausted and not writing, he made a deal with his father. Isaac would pay for his son to continue with the book-keeping program at Howard Payne Business College, and afterwards, would support him for a year whilst he tried to make writing a successful job. If he failed, he’d take a book-keeping job in town. Howard went back to Brownwood and his friends. He caught measles late that year, 1926, and had to spend two months in convalescence, but in the summer of 1927, he completed the course.

During the course, he devised and worked on “The Shadow Kingdom”, the first story of Kull the Conqueror. It was the first time that anyone had successfully combined fantasy, horror, mythology, high action, battle, swordplay and historical romance. In the process, he created the genre that would go on to be called Sword and Sorcery. He successfully submitted the story to Weird Tales in 1927.

It wasn’t actually the first Sword and Sorcery story in print, though. In 1928, Weird Tales bought “Red Shadows”, the first Solomon Kane story they released. That was written in the same style, and they printed it late the same year, making it the first piece of Sword and Sorcery to actually be published.

“The Shadow Kingdom” was released early in 1929, and proved incredibly popular. Over the course of the year, Howard also published boxing stories with three other magazines – “The Apparition in the Prize Ring” with Ghost Stories, “The Pit of the Serpent”, the first of the Sailor Steve Costigan boxing tales, with Fight Stories, and “Crowd-horror” with Argosy, one of the most prestigious of the pulps. Both Fight Stories and Weird Tales were now regular outlets for his work, and he was finally able to go full-time. His deal with his father had paid off.

By 1930, Howard’s long-term fascination with history had begun to blossom into a passion for Celtic history and myth. Now aged 24, he started investigating his ancestry, and even learned a little Gaelic. He started writing stories about Turlogh Dubh O’Brien – which sold – and about Cormac Mac Art, which did not. A new pulp, Oriental Stories, attracted his immediate interest, and gave him a venue to explore middle age and renaissance settings for several series of tales that blended swordplay and battle with blended mysticism.

That same year, Weird Tales published H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Rats in the Walls”. Howard loved it, and wrote to the magazine praising it, particularly the sense of historicity imbued in its British setting. They passed the letter on to Lovecraft himself, who wrote a warm and grateful reply. The two quickly became pen-friends, and Lovecraft introduced Howards to his wider group of authorial acquaintances. The Lovecraft Circle were pulp authors and promising newcomers who attempted to look out for each other, help each other’s careers, and dabble in each other’s worlds. Through the Circle, Howard became interested in the Cthulhu mythos, and made several contributions. This was also where he was given his nickname of ‘Two-Gun Bob’, in deference to the rowdy Texan world he’d grown up in.

Then, in 1931, the Great Depression started to bite. Many pulps went bankrupt, and most of the ones that clung on were forced to change their procedures. Weird Tales survived where many of Howard’s other publishers did not, but they were forced to go bimonthly, and they started paying quite slowly. To make things worse, his bank collapsed, wiping out his savings, and the little he did retain was then obliterated when his next bank collapsed as well.

He went travelling around Texas early in 1932, and he was in a sullen, rainy border town on the Rio Grande when he first came up with the idea of a bleak, pitiless northern land named Cimmeria. The obvious inhabitant of such a place would be an equally bleak, pitiless barbarian – and his name was Conan.

Howard was a master of the pulp market by this time, and he set out to make Conan as commercially appealing as possible. He got home and settled on the idea of an over-arching Hyborean Age, a time of pseudo-history uniting themes – and places – from across his earlier work. The first Conan story was a reworking of a Kull piece that hadn’t sold. Howard ripped out the elements that had bogged it down, and revised what remained into a thrilling, vivid crowd-pleaser.

By the time Weird Tales printed “The Phoenix on the Sword”, in December of 1932, Howard had already written nine more Conan tales, along with “The Horror from the Mound”, the first Weird West story, which was published in Weird Tales the following year.

Conan was taking Weird Tales by storm, so after a bit of a break, Howard dashed off another set of simple Conan yarns in early 1933. He took on Otis Kline as an agent to help him expand into other markets, with the understanding that Weird Tales would remain his own personal relationship. Kline helped him sell a number of stories that had previously been rejected, and encouraged him to broaden his horizon. Over the course of the year, Howard wrote his first story about James Allison, a disabled Texan who recalled adventurous past lives, and he finally made good use of his El Borak Texan gunslinger character, transporting him to Afghanistan, where he grimly tried to keep the peace in the era of the First World War. Late in the year, he returned to Conan, and started to work earnestly on deeper, punchier stories than the ones he’d churned out some months before.

In 1934, now 28, he started work on “The Hour of the Dragon”, a Conan novel requested by a British publishing house who felt that there was no real market in the UK for short stories. Unfortunately, the company collapsed before they were able to get the book published, and Weird Tales took it to release in sections. Howard was becoming interested in westerns at this point though, particularly humorous yarns and tall tales.

Since Weird Tales was well behind on their payments, he decided to pursue this new fascination. Action Stories took the first of the Breckenridge Elkins stories, and loved it so much they had a new instalment of the series in every issue until significantly after Howard’s death. Other pulps started clamouring for similar work, and he created clones of Elkins for Argosy (Pike Bearfield) and Cowboy Stories (Buckner J. Grimes).

That same year, he started dating Novalyne Price, a former girlfriend of an old college friend of his who took a job in Cross Plains. Breckenridge Elkins quickly became the most successful series that Howard had ever written, and in 1935, he started work on an Elkins novel, “A Gent From Bear Creek”. He spent that whole year on his yarns, and earning more than he’d ever managed to before. Although his professional life was more successful than ever, his relationship with Price was on-again, off-again – she was ill because of overwork, and he was deeply distracted by his mother’s increasingly poor condition.

Finally, in 1936, his mother was hospitalised with no expectation of recovery. On the morning of June 11th, he and his father were by her bedside when a nurse explained that she would not be coming out of the coma she had slipped into. Howard had set his affairs in order months before. He excused himself, went out to his car, and shot himself fatally in the head. His mother died a day later.

It would be a mistake to put Howard’s suicide down to filial grief or – as some opportunistic predators have claimed, an oedipal complex. He had considered suicide repeatedly over the years. He saw society as brutal, and life as cruel, but understood that the freedom and supposed purity he yearned for were impossible in the age he lived in. He also had a genuine horror of getting old, and was no stranger to dark moods. So say, instead, that his mother’s survival to the age of 66 was what kept him tethered to the Earth long enough to leave us the work he did – and, in the process, to change fiction itself.

Look for the next instalment in the Life and Times of Robert E. Howard series in a couple of weeks. Then we’ll take a look at his various characters, where one particular barbarian will make an appeareance.

Tim Dedopulos

Tim is an author, publisher, and game designer with tons of experience. He’s writing the Life and Times of Robert E. Howard series for Conan.com.