Ask a casual viewer about 1982’s Conan the Barbarian and they’ll likely mention Arnold’s muscles, thunderous music, or James Earl Jones turning into a snake.

Ask a scholar, and you’ll get something else entirely: a brutal meditation on the nature of strength itself, wrapped in blood and delivered at sword-point. The film poses a deceptively simple question – what is the source of true power? – then spends two hours systematically destroying every comfortable answer.

The Riddle of Steel is the philosophical spine of a film that dares to ask what other fantasy won’t touch. While Tolkien’s heroes resist evil and Lewis’s children discover faith, Conan confronts something more primal: the raw mechanics of power before morality even enters the equation.

This is the deep dive into how one film smuggled hardcore existential philosophy into multiplexes, using broken steel and the Wheel of Pain to ask a question that modern fantasy still struggles to confront: When everything you trust fails, what makes you strong enough to continue?

(NOTE: This exploration draws from the following brilliant analyses across decades: David C. Smith’s Nietzschean readings at The Barbarian Keep; Francisco Miguel Ortiz Delgado’s examination of the Übermensch in Journal Etica y Cine; John Garlick’s psychoanalytic dissection at Mythic Scribes; The Cimmerian Blog’s Marc Cerasini; a number of discussions at AddFaith Forums and Filosofkongene.no; and a variety of academic perspectives on the concept of the “new barbarian” from ResearchGate.)

A Boy Watches His Philosophy Die

A father holds his son close in firelight, pressing a freshly forged sword between them. “No man, woman or beast of this world ought to be trusted,” he warns, his weathered hands guiding small fingers along the blade’s edge. Here – this steel – “the only reliable friend that you have.” Minutes later, that same sword shatters in Thulsa Doom’s grip. The father dies clutching philosophy turned to fragments. His killer claims the broken hilt as trophy while a boy watches everything he was taught to trust fail catastrophically.

This opening sequence of John Milius’s 1982 Conan the Barbarian births what the film calls the Riddle of Steel. Where other fantasy heroes inherit Excalibur or Sting, ancient blades humming with destiny, Conan inherits shrapnel and doubt. The question that will drive every frame forward isn’t spoken; it’s carved into a child’s psyche through loss. If steel breaks, if fathers die mid-promise, if trust itself proves lethal, then what actually makes someone strong?

Critics dismiss the film as “cheesy or nerdy, or an “overly macho” relic of the Reagan era. They see Austrian muscles and hear thunderous scores, then look away. Yet Milius and co-writer Oliver Stone crafted something far more unsettling: a thought-provoking mix of violence and philosophy that dares to ask questions most fantasy deliberately avoids.

Most fantasy begins with moral certainty, as the hero knows good from evil, even if they struggle to choose correctly. Frodo understands the Ring is corrupt. Harry knows Voldemort must be stopped. Their challenges lie in execution, not existential questioning. But Conan? He begins with nothing except proof that his father’s truth was a lie. The strong take from the weak. Steel bends to flesh. Trust kills those who offer it.

In a single act of barbarism, Thulsa Doom demonstrates a competing philosophy through destruction. Power flows not from honest metal but from something else entirely, something the boy chained to slavery must discover or die trying to understand.

The Wheel Grinds Out An Answer

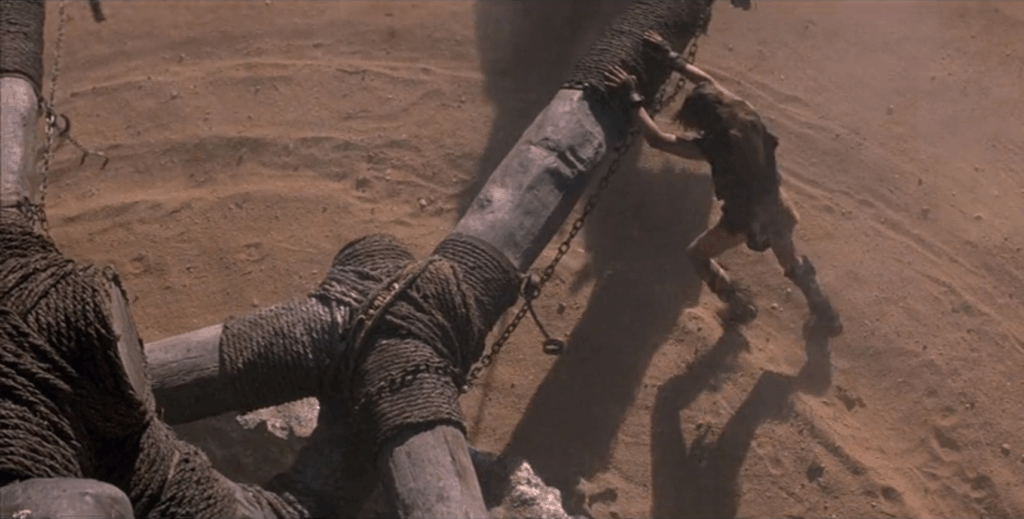

Years pass in circular agony. The Wheel of Pain claims children by dozens, grinding bones and spirits into dust across nameless seasons. Yet one grows stronger. Milius crafts “a masterclass in visual storytelling” here: no dialogue, no exposition, just flesh hardening against wood and time.

The sequence deliberately evokes the Greek myth of Sisyphus. Milius intended this “allegory” for humanity’s “universal human struggle” and “fruitless toil of life.” Children push, they circle, they die. Most collapse within months. Some last years before breaking. One survives decade after decade until survival itself transforms into something unprecedented. This “brutal apprenticeship…toughens and ‘re-creates’ Conan’s very being. His identity becomes “forged on this wheel just as surely as the steel of his father’s sword was forged in fire.”

What separates the survivor from the dead? Not superior morality. Not divine favor. Not even conscious choice. The Wheel selects through pure mechanical cruelty, and those who emerge carry its circular logic in their souls: suffering creates strength, weakness invites death, and meaning exists only in the refusal to stop.

Freed from the Wheel, made gladiator, then thief, Conan eventually faces his maker. Thulsa Doom lounges among drugged followers, having traded battlefield violence for something more insidious. “Steel isn’t strong, boy,” he purrs, gesturing toward a young woman on his temple’s edge. Without words, using only his serpent eyes, Doom compels her forward. She steps into air, plummeting to stone below. “Flesh is stronger!” He spreads his arms wide, the prophet validating his gospel through murder. “That is strength, boy! That is power!”

The demonstration positions Doo as Conan’s true creator: “Look at the strength in your body, the desire in your heart, I gave you this!”. By killing the father, by forcing the son onto the Wheel, Doom claims authorship over what emerged. His philosophy transcends material strength entirely, as true power means “the power to command,” the ability to “brainwash” others into willing self-destruction.

Why break bodies when you can possess minds?

Conan now carries two philosophies like twin scars: a trust in steel, and a command of flesh.

Which inheritance will he claim? The broken sword or the serpent’s whisper?

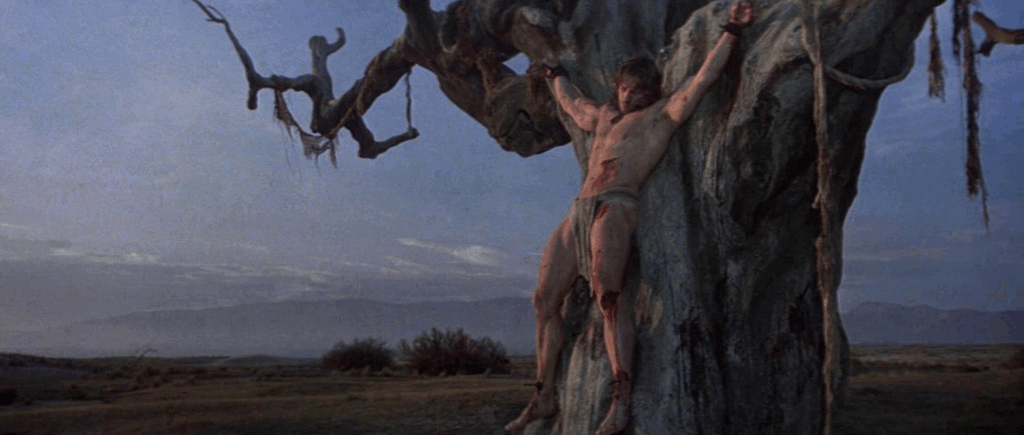

Then comes the Tree of Woe, where individual will meets its limit. Crucified, dying, Conan discovers that pure “willpower, almost got him killed.” The Wheel-forged strength that seemed absolute proves insufficient against dehydration, exposure, gravity itself. Salvation arrives through “love and friendship”, as Subotai and Valeria fight demons to drag him back from death’s edge.

The rescue complicates everything the film has built. If strength comes from solitary suffering, why does connection save him? If power means commanding others, why do these companions act freely, demanding nothing in return? The man who trusted only himself, who survived through isolated endurance, owes his life to bonds he never sought.

Healed but haunted, Conan approaches his final confrontation bearing the weight of three philosophies now: dead father’s matter, living enemy’s mind, and something unnamed that pulled him from the tree through neither steel nor flesh but through grace he didn’t earn and can’t command.

The Decapitation of Thulsa Doom as Philosophy

Temple steps, torchlight, and ten thousand followers waiting for their prophet to speak. Conan stands before Thulsa Doom holding his father’s broken sword. Doom’s eyes catch the fractured blade. Recognition flickers across ancient features before transforming into something worse than mockery: paternal pride.

“My child. You have come to me, my son. For who now is your father if it is not me?”

The question hangs between them like incense smoke. Doom doesn’t attack. He opens his arms, the same gesture that sent his follower plummeting to her death. Every word calculated to complete his final transformation from destroyer to creator, from enemy to father.

The film shows Conan “visibly contemplating” these words, and that hesitation contains multitudes. Two philosophies war across his features. Accept Doom’s claim and become the perfected weapon of another’s will–the flesh made strong through submission.

Or raise the broken steel his birth father trusted and prove… what exactly?

That failed philosophy can still cut?

Neither option satisfies.

Both answers died already: one in the snow of his childhood, one on the Tree of Woe. Yet Conan lifts the broken blade.

The decapitation takes three seconds. The implications resonate forever. By killing Doom with the shattered sword, Conan refutes his father’s thesis even while using it. Steel wasn’t strong. But broken steel still serves when wielded by sufficient will. The blade becomes mere “expression of the will directed towards a certain end,” nothing more than focused intention given metallic form.

Simultaneously, by killing the “flesh” that claimed superiority over steel, Conan destroys Doom’s antithesis. The prophet who commanded thousands through mind-control dies from primitive violence he claimed to transcend. His philosophy of mental domination proves helpless against someone who won’t be dominated. Doom’s flesh, for all its vaunted strength, parts before jagged metal guided by autonomous choice.

Victory belongs neither to steel nor flesh but to the “hand that wields.” This represents “a unity of all three” philosophies Conan wrestled with throughout the film. The synthesis Conan “contemplated on the tree of woe” emerges not through words but through action. In this decapitation, Conan performs the answer to the Riddle.

This creates what the film calls “Will to Power”. The Wheel taught endurance. The Tree revealed connection. The broken sword proved tools matter less than the force directing them. Combined, these lessons birth something unprecedented: a will that exists for itself, by itself, answerable to nothing beyond its own terrible freedom.

Blood spreads across temple stones. Doom’s head rolls past kneeling followers who came seeking submission and find themselves suddenly, horrifyingly free. Their prophet is dead. Their certainty shattered. The man standing above them offers no replacement scripture, no new father to follow. He burns their temple and walks away, leaving them to confront the same riddle he faced as a child watching everything trusted fail.

The Riddle Remains Unanswered

Years later, grey-bearded and crowned, Conan sits alone on a throne.

The film’s final image refuses triumph. No queen beside him, no celebrating court, no peace in those eyes that learned too young what breaking means. The Wheel “unchained” him from common weakness but left him lonely, as sovereignty’s price is paid in isolation. This is what becoming the answer looks like: you rule, you endure, you sit apart from those who never faced your questions.

In his conception of this character, Robert E. Howard understood something his literary descendants seem to have forgotten: strength emerges from the unyielding brutality of life.

Modern fantasy wraps its heroes in destiny’s cotton, ensuring they’re strong because they’re good, victorious because they’re right. Every farm boy discovers royal blood. Every prophecy promises triumph to the pure of heart. We’ve grown comfortable with strength as reward for virtue, power as proof of righteousness.

But what happens when fantasy drops its moral safety net entirely? When the only question is not “What’s right?” but “What works?” When strength comes not from being chosen but from choosing to continue when continuation seems impossible?

This Riddle of Steel was never meant to be solved. It’s meant to be lived, suffered, embodied. Each answer contains its own failure. The father’s sword breaks. Doom’s flesh bleeds. Conan’s will leaves him alone on cold metal.

Yet still the question persists, passed from the dying to those still deciding what they’ll trust when trust itself seems foolish.

Look at yourself.

The Riddle asks you: Would you survive breaking? And if everything you trusted shattered tomorrow, what would you forge from the fragments?

Lo Terry

In his effort to help Heroic Signatures tell legendary stories, Lo Terry does a lot. Sometimes, that means spearheading an innovative, AI-driven tavern adventure. In others it means writing words in the voice of a mischievous merchant for people to chuckle at. It's a fun time.