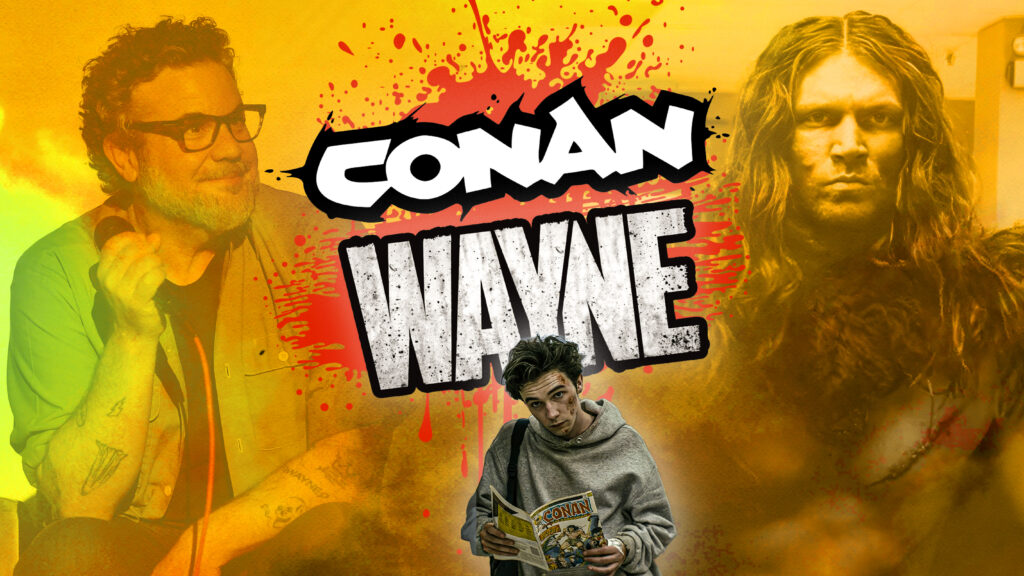

We sat down with Shawn Simmons, creator of the cult hit Wayne (now streaming on Tubi), for what was supposed to be a podcast interview.

Our editor Shawn Curley had swords on the wall. Simmons had a misprinted Conan comic he’s kept for years.

The conversation ran long, went deep, and landed somewhere neither of them planned.

By the end of it, we were looking at one show’s relationship to the Cimmerian, yes, but also realizing that creative properties like Wayne, that owe their lifeblood to the legendary barbarian are everywhere.

And so, what you’re about to read is our recounting of the interview’s contents, yes, but also the first installment of a new content series that that we can only describe as Conan – Minus Conan.

A New Way of Looking at the Wide World of the Legendary Barbarian’s Influence

On the pages of Weird Tales, Robert E. Howard created a frequency of storytelling so primal that it keeps showing up in places where nobody’s looking for it. You feel it in stories about people forged by hard places, driven by codes the civilized world doesn’t understand, burning through life with their fists and their grief and whatever scraps of love they can hold onto.

That frequency takes many forms: a great axe; a broadsword; and, sometimes, a plastic yolk and a beer can swung like a medieval flail.

Wayne – created by Shawn Simmons, now streaming on Tubi – follows Mark McKenna as Wayne, a teenager from Brockton, Massachusetts who sets out on a quest to recover his dead father’s stolen 1979 Trans-Am. He brings along Del, played by Ciara Bravo, is the girl he’s falling for. The premise sounds like a coming-of-age road trip. What you actually get is something far stranger and more savage: a story about a kid who reads Conan comics in his bedroom, sees himself in the Cimmerian, and charges into a violent world armed with nothing but an iron sense of justice and a total inability to walk away from a fight.

Understanding this premise, it’s not hard to see how Conan’s DNA is woven into every notch of the show’s skeleton. When Conan finally appears on screen in the season finale (did we mention that?), delivering lines pulled directly from Howard’s original prose, it lands because the whole series has been building that moment without you noticing.

Conan Minus Conan exists to chase down stories like this. The Hyborian Age casts a long shadow, and some of the most compelling work living inside it doesn’t carry the name on the cover. We want to find those stories, crack them open, and show you the connective tissue — for the Conan faithful who might discover something new to love, and for fans of these other worlds who might not yet realize where the blood comes from.

We’re starting with Wayne because our editor Shawn Curley sat down with Simmons for a conversation that made the case better than any pitch document could. What followed was an hour of two guys nerding out over Bêlit and beer can fights, Brockton parking lots and Cimmerian survival codes, the poetry of violence, and the specific way a father’s favorite movie can end up shaping his son’s entire creative life.

What became clear, almost immediately, is that Simmons didn’t borrow from Conan. He grew up inside a Conan story. He just didn’t have the language for it until he started writing one of his own.

Brockton from Wayne IS Cimmera

Brockton, Massachusetts gave the world two famous people, and both of them punched other men in the head for a living. Rocky Marciano trained at the Petronelli gym. Marvin Hagler came up through the same town, the same concrete. Shawn Simmons grew up in that gravity, with a father named Wayne (yes, the show is named after him) who was a fighter and a mechanic, a young dad who’d been raising his younger sisters since his own father left the family for the babysitter.

That father’s favorite movie was Conan the Barbarian.

“He was so into the violence of that thing,” Simmons told us, laughing. “He was like, ‘Yeah, and then the guy smashes his head with the hammer and then cuts his head off.’ And I’m a little kid at this point.”

It tracks. Howard, a boxer himself, modeled Conan’s physicality after the bruisers of the late ’20s and early ’30s. The character was born from the same place Wayne Simmonslived every day: a world where your hands were the first and last thing you owned. Brockton itself could pass for Cimmeria if you squinted. It’s gloomy, it’s depressing, and it’s live or die. You fight to survive, and that’s what shapes the person you become. There was a spot called The Rock (even the name feels lifted from a Howard manuscript) where the same guys would fight each other in recurring bouts.

Howard knew this kind of town. He grew up during the Texas oil boom in Cross Plains, a place where good men turned to booze, where violence was ambient, where a kid with a wild imagination could look around at the ugliness of mankind and start dreaming up barbarian kings. He never left that town. He wrote his way through it, story after story, pounding a typewriter in rural Texas the way Simmons’ dad pounded an engine block in Brockton.

The legendary Cimmerian comes from a place like this, too: a place hard enough to forge iron out of a boy. Howard’s version was Depression-era Texas. Simmons’ was working-class Massachusetts. The zip code changed. The forge didn’t.

During the conversation, Simmons shared a detail that made this whole thing feel like destiny: Simmons’ father once rode up on a horse to pick up his future wife. “Now that feels Conan,” Simmons said. He wasn’t wrong.

A Barbarian by Any Other Name

Wayne reads Conan comics. He keeps them in his room, studies them the way some kids study scripture. When the world gets ugly, he reaches for the Cimmerian the way another kid might reach for a hoodie or a baseball bat. Conan is his mythology, his operating system.

But here’s where Simmons does something sharper than fan service. Wayne thinks he’s Conan. He’s wrong.

The real Conan would rob a store without blinking. He’s a thief, a mercenary, a man who kills first and philosophizes about it later over a drink. Wayne, on the other hand, can’t do that. Wayne needs a victim before his fists start moving. Simply offensive attacking is beneath him while retaliation is not. There’s a code at work, but it’s not the barbarian’s code. It’s something closer to a kid who’s been hurt so badly that he can’t stand watching it happen to anyone else.

Simmons understood this tension from the jump. The show’s opening scene – where Wayne is getting beaten down by a group of kids and then throws a rock through their window – came from something Simmons witnessed as a child. A kid who got the crap kicked out of him, waited for the attackers to walk away, then stood up and threw a rock at them. Got beaten again for it. The last thing a kid like that will let you take is his pride. That’s not Conan’s pride, though. Conan’s pride comes from strength. Wayne’s comes from refusal.

The show knows this distinction matters. In the finale, a cop named Sergeant Geller, played by Stephen Kearin, sits Wayne down and tells him the truth: everything Wayne has done, every broken jaw and flipped car and bloodied knuckle, was for love. He reaches out through violence because nobody taught him another way to reach.

That’s a more interesting reading of Conan than most actual Conan adaptations have managed. Wayne uses Conan as a myth to survive, and the show gently peels the myth back to reveal something the kid doesn’t want to see: that the barbarian’s real quest was never violence. It was learning to be soft enough to let someone in.

I Live, I Burn, I Slay: The Appearance of Conan the Barbarian in Episode 10 of Wayne

Conan shows up in Episode 10 of Wayne as a character, on screen, speaking. If you’ve spent any time in fandom, you know how dangerous that is. The moment a show puts its hands on somebody else’s myth, a clock starts ticking. Get it wrong, and the people who love that myth will never forgive you.

Simmons knew this. He’d been thinking about Conan for the entire run of the show, building toward a moment where Wayne’s mythology steps out of the comic book and into the room. The actor he cast, Derek Theler, stood nearly seven feet tall. Heroic Signatures’ President Fred Malmberg sent the production a replica of the Father’s Sword form the 1982 classic to up the authenticity. The comic Wayne holds on screen is issue 52, “The Gods in the Crypt”, one of Simmons’ favorite covers, and one he fought to include because it mattered to Wayne.

Then there’s the speech. Simmons pulled directly from Howard’s prose, stitching together lines from the original stories into something that captured the DNA of the character without turning it into a museum exhibit. The crown jewel: “I live, I burn, I slay.” Howard wrote those words for “Queen of the Black Coast,” Conan’s declaration to Bêlit the pirate queen, the one woman he truly loved. In the context of that story, it’s a statement of purpose. In the context of Wayne, aimed at a teenage boy who’s confused love with war for ten episodes, it becomes a mirror.

That’s where the Del connection, portrayed by Bravo, cuts deepest. Bêlit is Conan’s great love, a woman who is fierce, bloodthirsty, sovereign. Del is none of those things. She’s kind. She flinches when Wayne kills a rabbit. But both women do the same thing to their respective paramores: they make the beast want to be something else. Simmons has said he always writes romance as the cure, and the parallel between Bêlit and Del is structural. Both love stories ask the same question about whether tenderness can survive in a person built for violence.

When Curley pointed out the Bêlit connection during their conversation, Simmons’ response was sharp: “But is he trying to convince himself?” He was talking about Conan. He could have been talking about Wayne. The whole show lives in that question of whether “I live, I burn, I slay” is a war cry or a cope, and whether the answer matters if the person saying it doesn’t know the difference.

Simmons told us he was terrified of getting this wrong. He wanted any Conan fan who felt protective the second they saw the character on screen to exhale. To feel respected. He wrote toward that audience because he is that audience, and because the kid at the center of his show is too.

Wayne Season 2 and the Call to Stream

With such a high bar to cross, the normal reaction for anyone is to ask what’s happening with Wayne from here on out. That is an interesting and unfortunate story.

Season 2 was written. Simmons had the script. Amazon gave every indication it was happening, then didn’t. Regime changes in the form of new executives inherited a show that was never theirs to begin with. And, you know the rest.

The story of Wayne season 2 would have followed picks up with Wayne in juvie, still making things harder for himself because someone took away the only person who taught him how to be soft. Del landed in the foster system, sharing a house with three other troubled girls, trying to build something that looks like a life. She’d been visiting Wayne. He told her to stop. In his head, the math was simple: he was ruining her.

Principle Tom Cole, played by Mike O’Malley, would have become Wayne’s guardian. Simmons described it as a breaking-a-dog story. Taming something feral by giving it a home. Conan would have shown up again, too. Simmons said he always would have found a way back in, whether in the middle of the season or at the end. The Cimmerian was never a cameo. He was load-bearing.

That story is still out there, unfinished. Wayne is streaming now on Tubi, and it has a habit of resurfacing (thanks to its habit of collecting new devotees who send Simmons twenty messages a day asking where the rest of it is). The show finds people the way Conan found readers in the ’30s: not through marketing, but through the specific recognition of someone who’s lived in a hard place and needed a myth to get through it.

If you’re a Conan fan who hasn’t watched Wayne, this is your entry point. Ten episodes, a Cimmerian speech that will make you sit up straight, and a creator who understands Howard’s work well enough to smuggle it into a completely different genre without losing a drop. If you love Wayne and have never picked up a Howard story, start with “Queen of the Black Coast.” You’ll meet Bêlit. You’ll understand Wayne’s struggle with barbaric vulnerability in a way you didnt before

Simmons keeps a Conan comic on his wall.It’s been there for years. When we asked about it, he didn’t hesitate: “Conan’s at the heart and soul of the show in a big way. He’s still hanging on my wall, and will never be taken down.”

Neither will Wayne.

Wayne is streaming on Tubi TV, and Eenie Meanie is on Hulu and Disney+.

Want more Wayne & Conan?! Head on over to our YouTube channel to watch the full interview with Shawn Simmons!

Lo Terry

In his effort to help Heroic Signatures tell legendary stories, Lo Terry does a lot. Sometimes, that means spearheading an innovative, AI-driven tavern adventure. In others it means writing words in the voice of a mischievous merchant for people to chuckle at. It's a fun time.