When Robert E. Howard unleashed Conan the Cimmerian on the world in 1932, he forever changed fantasy literature. But with dozens of stories featuring the iconic barbarian, where should new readers begin?

At Howard Days 2024, we cornered five Conan experts with a simple question: Which stories represent the absolute best of Howard’s Conan saga, and why? Their passionate responses revealed their personal favorites and also doorways into the true essence of a character often misunderstood by popular culture.

These five tales, handpicked by the scholars who know Howard’s work best, offer the perfect introduction to the authentic Conan: more philosopher than brute, more complex than conqueror, and far more compelling than any adaptation has managed to capture.

“Red Nails” – Conan at His Most Primal

If you’re looking for the quintessential Conan story that showcases Robert E. Howard at the absolute height of his powers, many experts agree that “Red Nails” stands as his crowning achievement. Written in 1936, this was the last complete Conan story Howard wrote before his death, and it crackles with an intensity that remains unmatched in sword and sorcery fiction.

In this tale, Conan and the warrior woman Valeria – fleeing from trouble as adventurers often do – discover a sealed city called Xuchotl in the midst of a jungle. Inside this labyrinthine structure, they find themselves caught between two ancient factions locked in a generations-long blood feud so bitter that they’ve entirely forgotten its origin. As the last survivors of a once-thriving civilization, these remnants fight with increasingly desperate savagery in halls marked by the red nails that count each kill.

Comic writer “Grim Jim” Zub doesn’t mince words about his assessment: “Look guys, I’m going to make it really simple, Red Nails is the best damn Conan story and don’t let anybody tell you otherwise! That energy, that lightning crackling across the typewriter.” The story indeed feels electrified, as Howard’s prose reaches a fever pitch that seems to vibrate off the page, propelling readers through one breathtaking sequence after another.

What elevates “Red Nails” beyond a simple sword and sorcery adventure tale is its perfect balance of action and thematic depth. “Valeria is an incredible character, just as strong as Conan, bringing him into this wild and strange adventure,” Zub explains. “You have two bizarre kingdoms clashing in these subterranean tunnels and labyrinthian spaces.” The partnership between Conan and Valeria presents one of the few times Howard wrote a female character who truly matches the Cimmerian in prowess and agency.

Howard scholar Paul Herman zeroes in on the story’s darker undercurrents: “Red Nails is the dark, violent, paranoid, the end of a civilization, how it just eats itself alive, how the hatred overwhelms everything else.” This observation highlights why the story resonates so powerfully even now—it serves as a microcosm for Howard’s views on the inevitable decay of civilization, a theme that runs throughout his work but finds its most concentrated expression here.

What makes “Red Nails” such a perfect introduction to Howard’s work is how it distills his core philosophical preoccupation into its purest form. The sealed city of Xuchotl represents civilization at its terminal stage: technically advanced but morally and spiritually bankrupt, turned inward upon itself in an orgy of meaningless violence. Against this backdrop, Conan’s barbarism appears not as a primitive state to be overcome, but as a vital, honest alternative to the decadence of so-called civilization.

For new readers looking to understand why Howard’s fiction continues to captivate audiences nearly a century after it was written, “Red Nails” offers the most concentrated dose of his unique vision: raw, unflinching, and utterly unlike anything else in fantasy literature then or now.

“Queen of the Black Coast” – The Emotional Heart of Conan

While many readers come to Conan expecting only bloodshed and adventure, “Queen of the Black Coast” reveals a more complex dimension to Howard’s iconic character. This story, published in 1934, introduces us to Bêlit, the fierce and beautiful pirate queen who commands a ship crewed by black corsairs along the coast of Kush. When Conan encounters her, he discovers the closest thing to true love he ever experiences in Howard’s original tales.

The narrative begins with Conan fleeing from authorities (a common situation for the Cimmerian) and jumping aboard a merchant vessel. When Bêlit’s ship, the Tigress, attacks, Conan stands alone against the pirates in such impressive fashion that the queen herself calls out: “You are no civilized man. I am Bêlit, queen of the black coast. Who are you to stand against me?” Impressed by his prowess and drawn to his wild spirit, she takes him as her lover and co-commander, beginning a partnership that spans years of adventuring.

Robert E. Howard scholar Mark Finn cuts to the heart of this story’s significance: “Conan finds and loses the love of his life. I think that’s what we’re dealing with in this story.” This emotional center sets “Queen of the Black Coast” apart from most other Conan tales, allowing readers to see vulnerability in Howard’s otherwise indomitable hero.

Sword and sorcery expert Bill Cavalier elaborates on this unique dimension: “Queen of the Black Coast, [is] the one where Conan discusses a lot of his philosophies and his outlooks on life and what may lie beyond.” Indeed, the relationship between Conan and Bêlit provides a rare window into the Cimmerian’s inner life, most memorably in his famous declaration: “I live, I love, I slay, and I am content.”

This philosophical aspect, as Cavalier notes, reveals Conan’s worldview more explicitly than perhaps any other story. When confronted with questions of mortality and meaning, Conan articulates a life philosophy that embodies the essence of Howard’s barbarism—immediate, vital, and untroubled by civilization’s anxieties about death and afterlife.

The story takes a dark turn when Bêlit’s quest for treasure leads the lovers to an ancient ruins guarded by a winged ape-creature, where tragedy strikes. Howard scholar Paul Herman observes: “Queen of the Black Coast people love because this is the one story where Conan falls in love, finds someone who actually is down there with him, and then gets to watch her die of her own greed, which is a great [object of] lesson for him.” This harsh education reinforces Howard’s recurring theme that civilization’s trappings—including the lust for gold—lead to downfall.

What makes “Queen of the Black Coast” essential reading is how dramatically it expands our understanding of Conan beyond the simple “barbarian” stereotype. Here, Howard shows us a man capable of profound attachment, who experiences genuine grief and loss. The story’s ending, with Conan setting Bêlit’s body adrift on a burning ship, delivers one of the most emotionally resonant moments in the entire Conan saga.

For readers who dismiss sword and sorcery as lacking emotional depth, “Queen of the Black Coast” stands as proof that Howard could write with genuine pathos while never sacrificing the primal energy that makes his work so compelling.

“The People of the Black Circle” – The Benchmark of Fantasy Fiction

“The People of the Black Circle” represents Howard at the height of his powers, crafting a novella-length adventure that seamlessly blends political intrigue, visceral action, and genuinely unsettling sorcery. Published in 1934 across three issues of Weird Tales, this story follows Conan during his time as a chief among the Afghuli tribesmen in the Himelian Mountains, a fantasy analog for the Hindu Kush.

The plot kicks into high gear when the king of Vendhya is assassinated through black magic by the sinister Master of Yimsha. When his sister, the Devi Yasmina, sets out for vengeance, her path crosses with Conan’s, who has his own mission: to rescue seven of his tribesmen held captive by Vendhyan authorities. What begins as a politically motivated kidnapping evolves into a desperate struggle against some of the most terrifying supernatural forces in Howard’s fiction.

For author and Howard scholar Bill Cavalier, this story sets the standard: “People of the Black Circle for me has always been the benchmark of fantasy writing.” Many critics and readers agree, often ranking it among Howard’s finest achievements in the Conan saga.

What makes the story immediately memorable is its explosive introduction of Conan. Cavalier vividly describes the scene that captivated him as a young reader: “There’s a point at the beginning of the story, where the Devi from Vendhya has come to the outlying areas and she comes to visit the governor there. And all of a sudden, Conan shows up, he grabs her up, jumps out the window onto his horse and hightails it out of there… that image of Conan bursting out of the window with the Devi in his arms and a sword, a kyber knife in one hand and the Devi in the other, that just, it spoke to a 16-year-old me like nothing else ever did.”

As the story unfolds, Howard demonstrates his unique approach to fantasy’s supernatural elements. Author John C. Hocking emphasizes this distinctive quality: “The first and foremost thing that jumps out at me is that the supernatural evil in this story is genuinely frightening. It would be not out of place in a horror story.” Indeed, Howard doesn’t present magic as mysterious light shows or abstract enchantments but as something visceral, physical, and deeply disturbing.

Hocking highlights one particularly memorable scene that exemplifies this approach: “The sequence in which one of the ears of Yimsha just reaches up and says, ‘I think I’ll take your heart, Karim Shah.’ And Karim Shah’s breast bursts open and his heart flies across the room and smacks into the hand of the wizard. It blew my mind when I first read it.” This brutal, corporeal manifestation of magic sets Howard apart from his contemporaries and many who followed, giving his supernatural elements a visceral impact rarely matched in fantasy fiction.

What makes “The People of the Black Circle” essential reading is how it showcases Howard’s revolutionary approach to both action and the supernatural. Unlike the sanitized magic systems of much modern fantasy, Howard’s sorcery is corrupting, horrific, and feels genuinely dangerous. Similarly, his action scenes possess an immediacy and physical reality that make readers feel every sword stroke and desperate gambit.

For newcomers to Howard’s original Conan stories, “The People of the Black Circle” offers perhaps the most complete expression of what makes his work special: prose that thunders with kinetic energy, magic that disturbs rather than dazzles, and a protagonist whose barbaric vitality stands in stark contrast to the decadent civilizations and corrupt sorcery he confronts.

“Beyond the Black River” – Howard’s Philosophical Masterpiece

Written later in Howard’s career, “Beyond the Black River” represents a significant shift in his approach to the Conan saga. Published in 1935, this story finds an older, more experienced Conan serving as a scout for the kingdom of Aquilonia on its frontier with the Pictish wilderness.

In this narrative, Aquilonia is expanding westward, building forts and settling pioneers beyond the Black River into Pictish territory. When a Pictish shaman unites the typically fractious tribes against this encroachment, Conan and a young settler named Balthus find themselves in a desperate struggle not just for their own survival, but for the fate of the frontier itself. What unfolds is less a traditional adventure and more a meditation on the nature of civilization’s endless conflict with what it deems “barbaric.”

Howard scholar Jeff Shanks identifies this story as particularly significant in Howard’s canon: “I think that one of the most powerful stories that really captures a lot of what Howard was trying to do with his work, captures a lot of his own ideologies and philosophical ideas about humanity, is in Beyond the Black River.” Indeed, this tale seems to crystallize Howard’s lifelong philosophical ideas in a way his earlier, more action-oriented stories could not.

The setting itself serves as a powerful vehicle for these themes. As Shanks observes, “It’s very much, in some ways, feels like a frontier story in the United States, in America, like Last of the Mohicans by James Fenmore Cooper.” This parallel with American frontier literature allows Howard to engage with questions about colonization and its consequences in surprisingly nuanced ways.

Shanks highlights this unexpected quality: “And so in some ways, it’s interesting because it’s almost a post-colonialist story. It’s very critical, in some ways, of colonialism, or at least cynical about colonization, which is not something that you would normally find in pulp fiction in the 1920s and 30s when Howard was writing.” Howard doesn’t present the Aquilonian expansion as an unqualified good, nor does he portray the Picts as simple savages. Instead, he depicts a complex clash of cultures where neither side can fully claim moral superiority.

In this story, Conan himself occupies a unique position as someone who can move between these worlds. Neither fully part of civilization nor aligned with the wilderness-dwelling Picts, he represents a third way as a barbarian who understands both worlds but is captured by neither. This liminal position allows him insights that characters fully embedded in either civilization or “savagery” cannot access.

The philosophical heart of the story emerges most explicitly in its famous concluding lines, delivered by a character reflecting on the frontier’s ultimate fate: “Barbarism is the natural state of mankind. Civilization is unnatural. It is a whim of circumstance. And barbarism must always ultimately triumph.” As Shanks notes, this statement has become one of the most quoted and discussed aspects of Howard’s entire body of work.

For readers seeking to understand the philosophical depth beneath Howard’s pulse-pounding action, “Beyond the Black River” offers the clearest window into the mind of an author whose work continues to resonate far beyond the pulp magazines where it first appeared.

“The Tower of the Elephant” – The Story That Defined the Hyborian Age

“The Tower of the Elephant” stands as one of the earliest Conan stories, published in 1933, yet it remains among the most beloved and frequently anthologized of Howard’s works. In this tale, we meet a young Conan, still in his thieving days, as he attempts to rob the mysterious Tower of the Elephant in the city of Arenjun, the infamous “City of Thieves” in the kingdom of Zamora.

The narrative begins in a thieves’ den where Conan, still new to civilized lands, hears about the supposedly impregnable tower of the dreaded sorcerer Yara and the magnificent jewel it contains: the Heart of the Elephant. With characteristic boldness, Conan decides to attempt what seasoned thieves consider impossible. His nighttime infiltration of the tower leads him not just to treasure but to an encounter with something utterly outside his experience: Yag-Kosha, an imprisoned being from beyond the stars with the body of a man and the head of an elephant.

What follows is one of fantasy literature’s most unexpected turns, as this seemingly monstrous creature reveals himself to be not a demon but a victim, telling Conan a tale of cosmic travel, betrayal, and centuries of torture at the hands of the sorcerer Yara. The story culminates in an act of mercy and justice as Conan helps Yag-Kosha achieve both vengeance and release from his suffering.

Howard scholar Patrice Louinet distinguishes this story from what he considers more formulaic Conan tales: “I like it because, well it’s not a potboiler… But among my top 5 fairy stories, I start with the Elephant because obviously with the Elephant, you’ve never read anything like that.” This uniqueness remains evident even today, but as Louinet notes: “And that’s today, imagine someone reading that in 1933, you would think, wow, what is this?”

Beyond its narrative innovations, “The Tower of the Elephant” holds special significance in the development of Howard’s world-building. This story marks the point where Howard’s creation evolves from a series of isolated adventures into a coherent secondary world with its own geography, history, and cultures. Louinet explains: “When he wrote Tower of the Elephant on the heels of [writing the Hyborian Age essay], he incorporated lots of stuff from the Hyborian Age into that story.”

For new readers, “The Tower of the Elephant” offers perhaps the most accessible entry point into Howard’s work. At once straightforward in its premise yet surprising in its execution, compact in its length yet vast in its implications, it showcases all of Howard’s strengths as a writer while avoiding some of the more dated elements found in other stories. In barely 8,000 words, it establishes both the Hyborian Age as a setting and Conan himself as a character more complex than the “barbarian” label might suggest, for he is all at once curious, adaptable, and governed by his own sense of justice rather than mere self-interest.

These five stories reveal why Howard’s creation continues to captivate readers nearly a century later. Beyond the blood and thunder lies a character of surprising depth and a worldview that still challenges our assumptions about civilization and human nature.

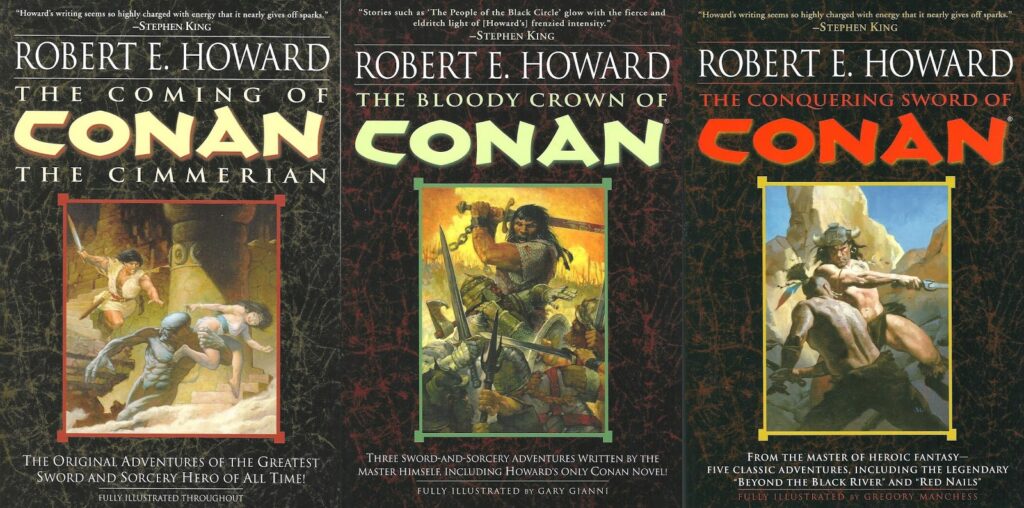

Ready to experience the raw power of Howard’s original vision? Start with these five essential tales, available in “The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian” collection from Del Rey or the comprehensive “The Complete Chronicles of Conan” from Gollancz. These definitive editions present Howard’s stories as he wrote them, free from later editorial changes, with the prose that thundered from his typewriter in Cross Plains, Texas.

The authentic Conan awaits you on the page, where Howard’s unforgettable voice brings the Hyborian Age to vivid life. Once you’ve experienced these classics in their pure form, you’ll understand why they’ve inspired generations of readers, writers, and artists.

By Crom, your journey into Howard’s world has only just begun!

Lo Terry

In his effort to help Heroic Signatures tell legendary stories, Lo Terry does a lot. Sometimes, that means spearheading an innovative, AI-driven tavern adventure. In others it means writing words in the voice of a mischievous merchant for people to chuckle at. It's a fun time.